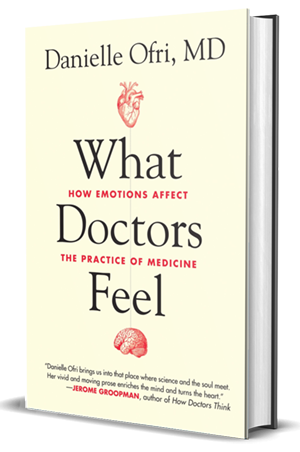

NYU Stories review of “What Doctors Feel”

by Eileen Reynolds

NYU Stories

Have you ever seen your doctor cry? It happens more than once in What Doctors Feel (Beacon Press, 2013), Danielle Ofri’s moving exploration of the often-ignored emotional underpinnings of medical practice. In the book, Ofri describes one young doctor who becomes numb to patient suffering after watching a newborn die in her arms, another whose adrenaline-addled mind goes blank when he’s asked for a simple Tylenol prescription, and a third who self-medicates with alcohol until substance abuse begins to interfere with her work. That physicians are often stressed and overworked is no secret, but Ofri provides a rare glimpse of the effects of shuttling from patient to patient without being allowed to process the powerful feelings—fear, anger, grief—that naturally arise when lives are at stake.

But the book isn’t simply a collection of horror stories. Ofri suggests a few relatively simple changes—from encouraging doctors to apologize for mistakes to tempering gallows humor—that can go a long way to repairing bruised relationships. And, by drawing from interviews with other physicians as well as her own 20 years of experience caring for patients at New York’s Bellevue Hospital, she provides many examples of the intimate, poignant, and sometimes tearful moments shared between doctors and patients.

We talked with Ofri, assistant professor at NYU’s School of Medicine and editor-in-chief of the Bellevue Literary Review, about her call for reform.

You use a musical term—basso continuo—to describe the emotional current underlying doctor-patient interactions. What’s the connection?

In Renaissance music, there’s always this ongoing bass line that just kind of makes the floor of the music. The emotional relationship is the pulse, the heartbeat, underneath all of our interactions, and if it were gone, you would notice its absence greatly. If you have symptoms and you type them into Google, you can get a diagnosis—and probably an accurate one. But I doubt you would feel cared for. If we’re being cared for by our iPhone, we’re missing that underlying emotional connection that makes medical care care, and not just a printed-out prescription.

You write that many students have their idealism shattered in medical school. How can we better support their emotional health?

Not every student who comes gets spit out as a callous, jaded cynic, but a not insignificant number have some lasting damage. Drug and alcohol use is very high among physicians. Suicide rates are the highest of any profession. I think that this is the kind of thing that we can’t address in a classroom or in our mission statements. If you hear it in a lecture hall, it only has minimal impact. But if you see your attending physician behaving in a way that makes you say, “ah, that’s how I want to be as a doctor,” or you see someone behaving in a way that makes you think, “God, I would never send my mother to this doctor,” those are the behaviors that create the environment in which our students train.

Should medical residents be required to speak with therapists?

I don’t know if mandatory therapy would go over so well. But what if one noon conference per month were devoted to this? Not when they send in a gray-haired social worker with a British accent and a pizza pie to talk about feelings, but when a department chair or division chief—someone in a white coat who does actual doctoring—sits down and says, “Gosh, here’s a big error I made,” or “This was the roughest part in my training.” That has resonance for a student.

What’s the role of the apology in medicine?

Many doctors are afraid that if they apologize for an error, that could be used against them in a suit, which is a well-founded fear. But part of this is moral decency. When we mess up, we need to acknowledge it. For doctors and nurses, acknowledging errors is a big part of healing ourselves. And studies show that patients are much less likely to sue if their doctors apologize.

What can a patient do to ensure a productive, satisfying doctor’s visit?

One thing a patient can do is prioritize concerns. When a patient comes in with 50 complaints at the same time, it’s not physically possible to give every issue its due. But if they say, “I have a lot that’s on my mind, but here are the two things I want to make sure we get to,” that really helps me.

You write about your early career in such vivid detail. Did you keep a diary?

I wish. I had a colleague in residency who kept a diary, but I was, I think, lazy. I also think it was too close to the emotional bone to write about at the time. I’ve probably forgotten the 10,000 blood pressure checks I’ve done, but the truth is you don’t forget patients that have these intense experiences with you. When I said to doctors, in interviews for this book, “Tell me what made you the doctor who you are,” not one person said “Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine.”They all talked about patient experiences which they could recall in incredible detail.