JAMA review of the Bellevue Literary Review

by Susan Arjmand

JAMA

The Bellevue Literary Review, published by the Department of Medicine at New York University Medical Center, was the first literary journal of its kind and holds a respected place among medical humanities scholars and those who write of medicine and illness, healing, and the human body. Bellevue, the oldest public hospital in the United States, may represent a natural starting point for reflection on these issues, and over the years (the review was founded in 2000) the editors have produced a journal of uncommon literary quality.

The spring 2011 issue is no exception. The review offers the BLR Literary Prize for the best writing in the categories of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction, and winners of the prize are included in this collection. It also includes a book review section and notes on the contributors. I found myself referring again and again to these brief biographies of authors, because in many instances the stories were so powerful I wanted to know more about the person who wrote them. As with the best fiction, the reader can end up wondering whether these events happened in the author’s life; whether the author knows people like the characters in the story.

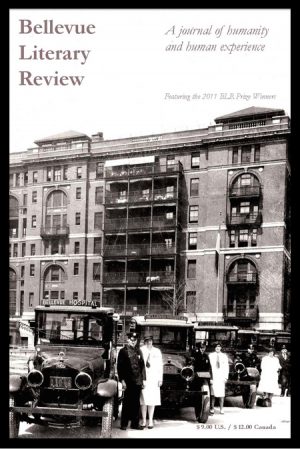

The photograph on the cover of the spring issue shows the Bellevue ambulance service and hospital in the 1930s. Readers are likewise offered cover notes about a long-serving physician at Bellevue who started his career in the ambulance corps as an intern during this era. The choice of photograph and story provides the reader a chance to reflect on the similarities and differences in medicine and society between that time and this. This description of a physician who began his career in the Bellevue ambulance service in the 1930s and published his reflections after a half century of service to that hospital in 1999 prompts the reader to contemplate the vast changes he must have witnessed.

The photograph on the cover of the spring issue shows the Bellevue ambulance service and hospital in the 1930s. Readers are likewise offered cover notes about a long-serving physician at Bellevue who started his career in the ambulance corps as an intern during this era. The choice of photograph and story provides the reader a chance to reflect on the similarities and differences in medicine and society between that time and this. This description of a physician who began his career in the Bellevue ambulance service in the 1930s and published his reflections after a half century of service to that hospital in 1999 prompts the reader to contemplate the vast changes he must have witnessed.

However, a review of some of the clinical situations depicted in these stories reminds readers of the unchanging nature of suffering, social exclusion, loneliness, and loss. In this way, the journal succeeds in encouraging the reader to recognize the universality of some of these life experiences, by juxtaposing contemporary writings with images of the past. Readers encounter descriptions of specific clinical situations in the context of the individuals who live with them: infant demise, the loneliness of a caregiver, a disabling stutter and the resulting social isolation, severe scoliosis, religious fanaticism, domestic violence, sexual assault, the dependence and vulnerability of disabled persons, self-mutilation, terminal disease. The clinical situation is sometimes the focal point of the reflections but often is the shadow in the background of the essential story of these characters’ relationships to each other. This shadow is so large that it becomes a character unto itself in these stories, providing even more emotional heft and poignancy.

No doubt because of the reputation of the journal and its prestigious prizes, this issue includes the works of many accomplished and talented writers, resulting in evocative and deeply moving pieces. The way in which real-life experiences lend themselves to nonfiction may seem straightforward, but the writer’s experience of baring the soul in the process of truth-telling is difficult and elusive. For this reason, writers find safety in fiction, where “the most truthful truths†can sometimes be found. In describing the human condition in this way, the writer can create a small space between real life and make believe and, in so doing, find more freedom to express the pain, vulnerability, and joys of life.

The editor in chief of the Bellevue Literary Review, Danielle Ofri, refers to fiction as the “great lies that tell the truth.†This collection offers many fine examples. It is recommended for medical humanities scholars and educators who might choose to use some of these stories or poems to promote discussion and reflection. It also will benefit physicians and other health care personnel who grapple with the sadness, frustration, and inspiration found in caring for others. Moreover, these writings will be useful to patients and those who experience illness or loss. There is comfort to be found in the reminder of the universality of these experiences.