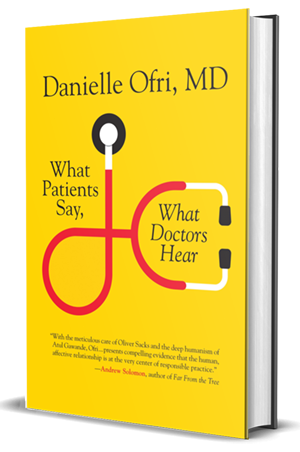

Washington Post Review of “What Patients Say, What Doctors Hear.”

Measuring the Wonders of an Empathetic Ear in the Doctor’s Office

by Libby Copeland

Washington Post

If you’ve switched physicians in search of someone more caring or left an exam feeling unseen and unheard, you will find much to appreciate in Danielle Ofri’s perceptive book “What Patients Say, What Doctors Hear.†The shortcomings of the patient-doctor relationship are on full display as Ofri probes what goes wrong in the exam room and tallies the impact on the care we get.

We often think of medicine in terms of numbers and statistics. How many possible diagnoses are there for this mystery ailment? What’s the success rate for this surgery, or the likelihood of remission after chemotherapy? We rightly want our doctors knowledgeable about the latest treatments and side effects.

But Ofri makes a compelling case that patient-doctor communication in the exam room is as crucial to diagnosis and treatment as expensive tests and procedures. Offering empathy, asking open-ended questions, involving the patient in a treatment plan and checking again and again to make sure patients understand are all key to making the sick better, she writes.

Ofri, a physician at New York’s Bellevue Hospital and a professor at the New York University School of Medicine, delves into medical research and draws on her years of practice and observation to illuminate vital aspects of the patient-doctor relationship: Good communication lowers anxiety, raises patient confidence and makes us more likely to adhere to treatment plans. Longer visits with primary-care doctors are correlated with fewer malpractice suits. Doctors who listen well are more likely to uncover hidden causes of illness, such as sexually transmitted diseases. In one study, back pain patients receiving electrical stimulation experienced far more pain relief when accompanied by a physical therapist who was a good listener. Research shows that patients who visit more empathetic doctors even shorten the duration of their colds by more than a day.

We’ve known for decades that doctors who offer empathy, build trust and set expectations help their patients fare better. As far back as 1964, a study conducted with abdominal-surgery patients illustrated what Ofri calls the “demonstrable effect of the simple act of talking.†Before surgery, half of the patients were visited by an anesthetist who said pain afterward would be normal and would last a limited amount of time, and explained how patients could relax their muscles to lessen the pain. These patients needed half the pain medication of others who didn’t receive a pain talk. If we are an overmedicated nation, better communication would seem an easy and cheap way to relieve that burden — except that listening takes time, and doctors don’t usually have that.

Ofri’s insights are particularly instructive as the medical profession increasingly suffers from tight schedules, packed waiting rooms and tightwad insurance companies. With patient-doctor communication more important than ever, Ofri shows how it gets fouled up, pointing to unspoken assumptions, rhetorical differences and language barriers. (And she’s not talking about nonnative speakers of English; medicalese is its own language, impenetrable to laypeople.) When patients go to the doctor, Ofri writes, they’re inclined to tell the “story†of their illness, from beginning to end, while doctors are trained to look for the “chief complaint.†Little wonder, then, that research shows “doctors typically interrupt patients within 12 seconds.†The difference in speaking styles sets up an experience in which patients feel rushed and unheard, and doctors feel impatient about their rambling patients. Too often in exam rooms, we are speaking past each other.

An open, welcoming physician can draw out crucial information that otherwise might lie hidden. Ofri recounts examining a woman with a tense smile who described the pains she had in various parts of her body. After the woman left the exam room, she returned and, clutching the doorknob, said, “Doctor?†She hesitated. “ ‘Do you think it’s possible . . .’ She hesitated again. ‘Do you think it’s at all important that these are the same spots where my boyfriend shot me with a dart gun?’ †The “hand-on-the-doorknob phenomenon is . . . well known to all doctors,†Ofri writes. “A physician can proceed assiduously through a detailed history and physical with a patient, but it is only when the patient is halfway out the door that the important information spills out.†Ofri invited the woman back into her office so they could continue talking, clock be damned.

Ofri seeks to humanize a profession often seen as haughty, privileged, uncommunicative and indifferent to criticism. She’s also sensitive to her colleagues’ resistance to “hokier-sounding soft stuff†such as communication, empathy and connection. “Something that simple and intuitive, something that doesn’t require specialized knowledge, can feel threatening to a physician who has spent a decade training to acquire unique medical knowledge. . . . There’s something vaguely discomfiting to realize that the techniques shamans used centuries ago can sometimes be as effective as our pharmaceuticals backed by million-dollar mega-trials.â€

But, as Ofri’s compelling argument makes clear, modern medicine could benefit from a better understanding of how human beings like to be treated when they’re at their most vulnerable — sick and confused and naked save for a thin paper gown. If only doctors could bill for listening.