A Bellevue Doctor on Trump, Exam Room Conversations and Her New Book

by Nicole Levy

DNA Info.com

Danielle Ofri’s patient, a 37-year-old bodega worker and single mother, ostensibly came to the Bellevue internist seeking a cure for ringworm.

Wearing a baseball cap to conceal her patchy scalp, she also made casual mention of the mysterious aches and pains afflicting her stomach, left knee, right shoulder and the back of her head for six months. But a physical exam turned up no signs of injury or known disease.

It was only as the woman turned to close the door on her way out of the office that the truth emerged in the form of a question: Could it be relevant, she asked, that all the parts of her body that hurt were the same spots where her boyfriend had shot her with a dart gun?

“I wanted to kick myself,” Ofri recalled. “How could I have missed this? Why didn’t I catch the tautness in her smile? Why hadn’t I keyed into the withdrawn demeanor coupled with the seemingly random symptoms?”

A 2004 study of 2,000 videotaped patient visits by a group of European researchers found that such “unexpected agendas” as domestic violence come to light in one out of every six to seven visits; doctors who spent a greater portion of the time listening were the most successful in unearthing buried patient concerns.

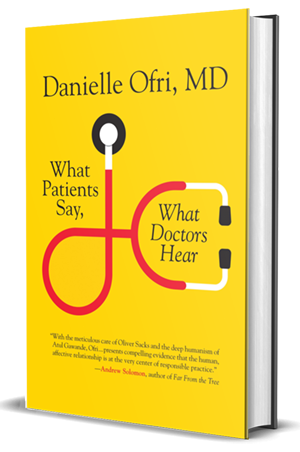

Ofri draws on anecdotes and evidence like these in her new book, “What Patients Say, What Doctors Hear,” to argue that, even as technology advances, conversation between patients and doctors remains the “most potent diagnostic—and therapeutic—tool in medicine.”

Considering the information, diagnoses, treatments and relationships that arise from simple conversation is “far more intricate, powerful and flexible than most of our other medical technologies, which generally do only one thing in one way,” Ofri writes in her book, which hits shelves Feb. 7.

A medical practitioner at Bellevue Hospital in Kips Bay for a total of 22 years, Ofri is also an associate professor of medicine at NYU and the author of five other books about life as a doctor. She lives within walking distance of the hospital with her husband, three kids, and an aging dog, and splits her time between writing, seeing patients, editing the Bellevue Literary Review and learning to play the cello.

DNAinfo New York spoke to Ofri about what President Donald Trump’s administration means for her patients, the lessons she’s learned on the job, her loyalty to Bellevue, and New York City’s changing medical landscape. You’ll find her answers to our questions below:

Bellevue is a public hospital that serves a disproportionately low-income and immigrant patient population from neighborhoods that are, on average, medically underserved. What kind of an impact do you think Trump initiatives like the repeal of the Affordable Care Act and the refugee ban will have on your patients and your practice there?

Bellevue is a safety net hospital. We take care of many people who are uninsured, so the Affordable Care Act helped insure many of our low-income patients. A repeal is going to be a huge hit economically. I also worry that my patients will drop out of care, because when you don’t have insurance, you say, “Well, I don’t want to go, because it’s going to cost me.” I worry that patients are going to start skimping on basic preventative care and end up in the E.R. when they’re really sick.

The second area where I see the [Trump administration] really affecting things is the nervousness about immigration. Many of my patients are immigrants and many are undocumented. The whole level of anxiety of not knowing has just added angst to so many people that I take care.

With the proliferation of less-than-plush health insurance plans, patients have to be more aware of the medical costs they’re accruing. How has that changed conversations in the doctor’s office for you?

Patients often, when I order a CT scan, will say, “How much will it cost?” And I feel like a complete idiot, because I have to say, ‘I don’t know.” It depends on their insurance, and I just can’t answer their questions. It leaves this big black hole.

I try to focus on the things that we can control: I remind my patients that so much of our illnesses can be modified by what we eat and our activity, especially for chronic illness like diabetes, hypertension, obesity, heart disease.

In your book, the issue of time in the exam room pops up repeatedly. What have you found to be the best way of using the time you do have?

Let’s say this patient has an ill child in Guatemala. That’s the most important thing for them, much more important than hypertension. So if I take a minute to write that down, the next time I can say, ‘How’s your daughter in Guatemala doing?’ Because I know that that’s number one in their mind, and we need to talk about that before we get to hypertension.

If you invest in trust and good relationships, then I think the patient is more willing to listen to what you have to say about their medication, and more willing to tell you, “Doctor, I’m actually not taking the medication, because it ruins my sex drive, or makes my mouth dry or makes me pee at night.”

You’ve written that patients have been some of your best teachers. What’s the most useful lesson they’ve taught you?

I think the lesson I’ve gotten most from patients is that first impressions and snap judgments are often incorrect. Especially patients who show up belligerent and angry, which many patients do. By the time I see them, they’re been given the runaround tenfold, both in our hospital and the medical system in general.

I’ve learned that if I don’t take it personally — which is not easy all the time— and really try to be respectful and understanding, often that initial anger will recede.

Speaking of first impressions, your book discusses ways to address our unconscious biases. Were you thinking about the world beyond Bellevue when you wrote that passage?

I would say this whole election process has given me a lot of pause. In professional medicine, there’s not a lot of African-American representation. I really wanted to start thinking more about that, so I’ve been listening to podcasts and reading different news sources about the African-American experience, because I realize that there’s a lot I don’t know … The election really made me think hard about that.

You’ve worked at Bellevue for more than two decades now, including your residency. What’s kept you there?

It’s the most amazing place in the world. The people who choose to work there are some of the smartest, most hard-working people I know. I meet patients from all over the world every day — I always learn about new countries and languages I didn’t know about. But also I feel like I can serve patients and have more effect. When I worked in the private sector, I was just one of a team of people they had available to them. Here, I might be the only medical professional a person sees. If I make a 10-percent extra effort, it makes a huge difference in their life.

Based on the cases you’re seeing at Bellevue, what do you think is the most urgent public health crisis in New York City today?

Diabetes has skyrocketed, and it’s not just at Bellevue, but really everywhere. Almost everyone I see has either diabetes or pre-diabetes and is battling weight. We’re starting to recognize that we really have to talk about lifestyle changes. We didn’t evolve differently in the last 20 or 30 years, but the way we eat has. I now spend almost every appointment talking about basic nutrition, something that was never part of [my] medical evaluation.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. If you want to hear from Ofri firsthand, you can attend at one of these appearances.