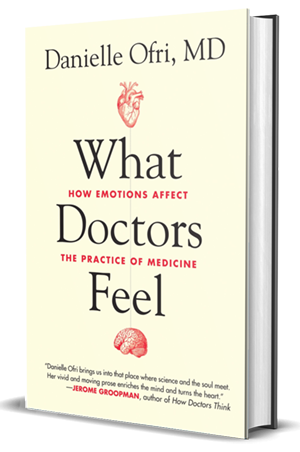

Boston Globe review of “What Doctors Feel”

by Dennis Rosen

Boston Globe

The emotional cost of witnessing human suffering, grief, and loss up close can be unbearable. This is something physicians struggle with regularly, no matter how far along they are in their careers. Danielle Ofri’s rich and deeply insightful new book, “What Doctors Feel,†explores this aspect of medicine, its impact on trainees and practicing physicians alike, and the effects that it has on the quality of care they provide to their patients.

Many might consider the physician’s cognitive skills, those of deductive reasoning and pattern recognition honed by years of experience, as the most important to the healing process. And indeed, it is very important that physicians acquire a solid knowledge base and know how to apply it to the clinical situation at hand. Jerome Groopman explained this very well in “How Doctors Think,†which examined how medical decisions are made by physicians, why they mostly succeed, and why they sometimes go spectacularly wrong.

Ofri, an internist and the editor of the Bellevue Literary Review, is also the author of three previous books exploring the physician-patient relationship. In “What Doctors Feel,†Ofri reminds us that the emotional aspects of the healing process are at least as important as the cognitive ones, and that when these are neglected or overlooked, the negative consequences to both patient and physician can be enormous.

Ofri notes that “the medical student observes that even the most thoughtful and humanistic intern operates under the brutal calculus that every minute spent on nonessentials simply prolongs the work.†And what, exactly, are these nonessentials?, she asks. “An in-depth conversation with a patient . . . a more thorough physical exam, to patiently explain the disease process to a family member . . . let[ting] a patient ramble on without interruption,†she answers.

It is obvious how essential Ofri recognizes all of these to be to the healing process, and she laments the well-documented attrition of empathy in medical students and residents as they advance with training. This is significant, for as Ofri points out, multiple studies have shown that physician empathy results in better patient outcomes.

One of the reasons that many of the young trainees lose their empathy is because the suppression of emotions becomes a useful defense mechanism for them as they are repeatedly exposed to awful things during prolonged periods of stress and sleep deprivation. With time, suppressing emotion can become second nature. However, it is only possible to bottle up emotions for so long before they erupt without warning and knock you off track. Ofri describes in simple yet heart-rending detail how this happened to her and to her colleagues. This is bound to resonate with every physician who reads the book.

“What Doctors Feel†is richly illustrated with personal stories and poignant vignettes about Ofri and many of the patients she’s cared for over the years. In these, she readily points out her own weaknesses and mistakes, and explains how she has learned from them, emerging, she feels, a better physician and person as a result.

Ofri adroitly balances presentation of her own experiences and those of others, with research into the emotional aspects of medical practice. The result is a fascinating journey into the heart and mind of a physician struggling to do the best for her patients while navigating an imperfect health care system that often seems to value “efficiency,†measured in dollars and minutes, more than the emotional well-being of either physician or patient. Her voice is one that deserves to be heard and listened to carefully, as what she describes carries great significance for all of us within the health care system, patients and healers alike. (from the Boston Globe)