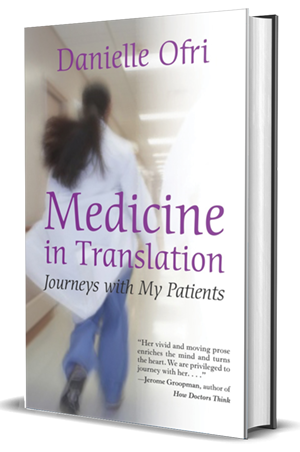

Fascinating Tapestry – “Medicine in Translation”

The threads of Danielle Ofri’s memoir, Medicine in Translation, come together in a fascinating tapestry, with shimmers of what it is to be a physician, a mother, a writer and musician, a person with opinions trying to open herself to a world full of differences. She writes well, and the stories she weaves here are by turns painful, funny, searching, and full of thoughtful interest in the human condition.

Ofri has been a doctor for twenty years at Bellevue in New York City, the oldest public hospital in the U.S. Through her eyes, we glimpse the stream of people coming through its clinic. She reveals enough of herself, as well, to give us insight into the daily and strenuous life of a doctor there, especially one who is genuinely engaged with both her patients and her family.

Bellevue serves a broad population. Ofri’s practice is inclusive, from torture survivor to illegal immigrant, Bangladeshi teenager to elderly Chinese couple. With current debate over immigration and health-care reform, there is much here to provoke thought and discussion. Yet the book is most keenly focused on how Ofri’s awareness expands as she goes the extra mile to know these individuals. She describes her efforts to learn Spanish, her encounters with hospital translators and mountains of paperwork, and the moments when she slows down and sees beyond a patient profile to the person. These are stories to wake us up to the diversity of human experience in our own country, and Ofri models an openhearted and wise response. Often she struggles to go beyond a thoughtless first reaction and reaches greater acceptance of her patients and herself.

Ofri includes a description of a year’s sabbatical in Costa Rica, where she let go of practicing medicine, focusing instead on her family, Spanish, and her cello. This could seem too large a digression from her hospital stories, but instead proves to be an important time of personal growth that informs her work when she returns to New York. The long vacation is important to renewing her energy for the hard work at Bellevue. It also leads to a deeper effort to know the people who come to her for medical support.

As she finds herself wanting to write their stories, she gains permission from some of her patients to delve more personally into their lives. Ofri spends time with them beyond strictly medical appointments and the fuller pictures that appear make them whole beings rather than just facts noted on a chart. Some might question the ethics of this overlapping of relationships, yet it seems clear that Ofri is better able to assess and assist them when she sees her patients in a fuller dimension.

Especially haunting are the people who have survived suffering at the hands of their fellow human beings. As Ofri balances objectivity and sensitivity, we share her horror at the sulfuric acid poured down a man’s throat, and also understand that her job is to find him the help he needs to move forward. Her tone never exploits pain in favor of the sensational. I was never overwhelmed, but rather led to understanding, and ultimately to awe at the resilience, kindness and bravery of these people. Threaded together, Danielle Ofri’s small interactions and sturdy efforts make, for her fortunate patients and for her readers, a fabric that warms and heals. This is not so much a book about practicing medicine as it is about practicing compassion. I won’t forget it.