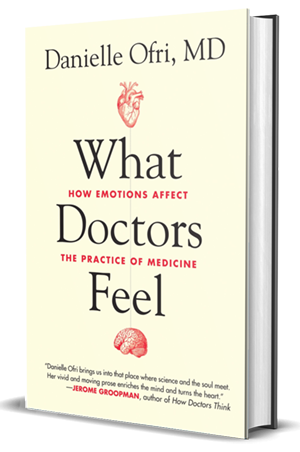

Review of “What Doctors Feel”

by Julie G. Nyquist

J of Chiropractic Medicine

It is a privilege to review the book What Doctors Feel: How Emotions Affect the Practice of Medicine by Danielle Ofri. This is Dr Ofri’s fifth book exploring medical training and doctoring. She is an internist with more than 20 years of experience in clinical medicine. In the “Introduction,†the author emphasizes that the book is “intended to shed light on the vast emotional vocabulary of medicine and how it affects the practice of medicine at all levels.â€

This is a book about the emotional side of being a clinician and includes illustrative stories gathered from Dr Ofri’s personal experience and interviews with other doctors about how emotions impact clinicians’ judgment and actions. This book aims to raise awareness in doctors and in patients about those emotions, especially the more troubling ones: fear, shame, grief, anger, and being overwhelmed or feeling burned out. In the “Afterword,†Dr Ofri explains that she chose these emotions because they “exert the strongest influence on medical care.†This is challenging subject matter. Thus, as you read this book you may not always feel comfortable nor will you necessarily agree with the thoughts or actions of the storytellers. Dr Ofri does not tell tales of perfect performance, but she does allow us to see inside of doctors and demonstrates an uncommon willingness to share her own actions and feelings. She opens herself up to us and shares the negative critique that she received after sharing some of her prior stories.

Although this book contains many stories, the story of Julia—a patient of Dr Ofri’s for more than 8 years—provides a continuous thread throughout the book. Julia’s story provides a break between chapters and is told in 7 parts, one after each of the chapters. In the “Afterword,†Dr Ofri shares that she selected this story to both honor Julia’s story and to “portray how emotions infuse and affect the doctor-patient interaction at every level.â€

Each chapter addresses a different emotional challenge faced by doctors. The book also points out how elements in our health care system impact doctors in very negative ways. These elements are highlighted by the stories of physicians: Sara, Joanne, Eva, Curtis, and others—some triumphed over adversity and their own emotional reactions to remain within medicine; some wrote their own books or articles to tell their stories, a catharsis of sorts; while at least one left medical practice. The stories lead into discussions, some brief, others more in depth, about the elements of our health care system and the place of medicine in society; these discussions are at the core of the emotional struggles of health care providers. Dr Ofri uses evidence from studies to describe the magnitude of the challenge in each chapter and to provide some hopeful examples of institutions that are making changes to their structures or instituting programs for learners and practitioners to help them cope, balance, and thrive.

Each chapter is like a journey into the hearts and minds of clinicians who are struggling with emotions triggered by the realities of medicine. The first 2 chapters, “The Doctor Can’t See You Now†and “Can We Build a Better Doctor?†explore empathy and honesty with self and the human struggle doctors face developing and maintaining empathy. Along with the stories of struggles with empathy, Dr Ofri also speaks about the well-documented phenomenon of trainee loss of empathy during their clinical training, and the impact of the “hidden curriculum.†She notes that faculty can help learners to build and maintain empathy throughout training both through their own demonstration of empathy and through curricular interventions that may help, including periodic group mentoring and training within a continuity setting.

Chapter 3, “Scared Witless,†reveals the fear and stress that can overwhelm a doctor, particularly during training. Fear can be “of the situation, of getting it wrong, of killing the patient, [or] of looking like an idiot†as Dr Ofri herself felt the first time she was assigned as the doctor in charge of running a “code.†After discussing the role of the amygdala on emotions, she discusses fear as a “primal emotion in medicine†and its effects on doctors throughout their careers. Although some training programs provide assistance by offering mindfulness meditation, stress management workshops, and support groups, a clear need for more such programs for trainees and practitioners was made evident.

In Chapter 4, “A Daily Dose of Death,†Dr Ofri focuses on grief and on the onslaught of sickness and death faced by many young doctors training within hospitals. She notes that grief is “an overwhelming emotion for anyone who faces tragedy†and ponders why medicine has paid it so little attention. She discusses how “with no time or space to give grief its due, burnout, callousness, PTSD and skewed treatment decisions are a risk.†Staff support groups may provide one answer with an example provided from the University of Rochester.

Chapter 5, “Burning with Shame,†is about guilt, shame, and the inevitable errors that clinicians will make. The chapter opens with a story of a medical error that Dr Ofri made as a resident, and at the end of the chapter she notes that shame prevented her from being able to tell that story for almost 20 years. She describes shame as “the elephant in the room†and recommends that senior clinicians set the tone for disclosure of errors without “shame†by sharing with learners their own stories of error and how they dealt with the shame. Finally, she writes that to prevent errors we must know about them and understand them, and emphasizes that “unless we can somehow defuse the shame and loss of self-definition that accompany the admission of medical errors, the gut instinct to hide error†will remain.

Chapter 6, “Drowning,†discusses disillusionment in medicine when ideals and reality are in conflict, and how doctors cope with the resulting emotions. Some of the issues are administrative and paperwork overload, time pressures, financial issues, family strains, and the letdown after training when the pace of “new†learning slows. She makes the bold statement that “disillusionment and frustration are nearly universal among doctors, at least to some degree.†This can result in symptoms of depression, stress, and burnout, as well as doctors exhibiting disruptive behavior, angry outbursts, or medical errors, or attempting self-medication that can result in substance abuse. Another result can be doctors who lack empathy. Providing a safe place for doctors to talk and share experiences may help, but it also requires “creativity, flexibility and commitment on the administrative side†in order to alter “the structural frustrations of medicine.â€

Chapter 7, “Under the microscope,†focuses on malpractice and the enormous emotional toll it takes on doctors and ultimately on patients. The system has improved but still leaves many doctors scarred and disillusioned.

I believe that the book fulfills its goal—to explore the role emotions play in the health care system, in the care of patients, and in the lives of clinicians. For those who train future clinicians, I believe it is an essential book. Education in the health professions, including chiropractic, is excellent at guiding trainees in developing the knowledge and skills needed to practice health care. However, the values that underlie great doctoring are often neglected, and the emotions that clinicians feel, especially the negative emotions highlighted in this book, may never be openly discussed.

This book provides a call to action, to every educator to find a way to arm young health care providers with emotional tools along with technical skills. Graduates need the tools to stay healthy, to maintain the empathy required for excellent and safe care, and to prevent burnout. It is also a call to every practitioner to push the health care system to evolve in a positive direction—to work to enhance provider well being, lessen administrative and paperwork burdens, and lower the barriers between doctors and patients.