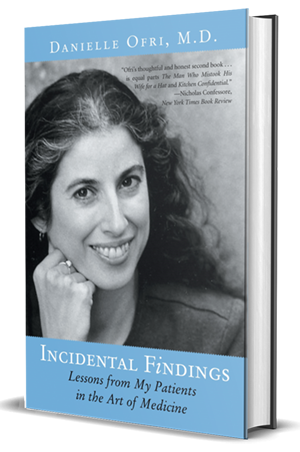

Prairie Schooner review of “Incidental Findings”

by Joshua Dolezal

Prairie Schooner

Danielle Ofri is a shaman. She might balk at the title as a medical doctor, yet her essays grapple with moments when traditional medicine has failed her, when science seems no more than empty ritual, and she feels as blind as her patients to the mysteries of health and illness. In such moments, Ofri instinctively turns to her patients’ emotional anatomy: the tumors of despair, the hot blood of hope, the pulsing will to live. She is constantly embroiled in the psychological crack-up that Joseph Campbell associates with the shamanic vision, when the “unconscious opens up, and the shaman falls into it.†The unconscious, for Ofri, is emotion—the force that gives her essays totemic weight. She understands illness as a narrative and the stethoscope as a device that is sometimes essential to the story and sometimes not. She engages the full arsenal of myth and science, and this makes her a powerful present-day shaman.

Incidental Findings is Ofri’s second book, chronicling her sojourn as an itinerant physician and her eventual return to Bellevue Hospital, where she now holds the dual titles of attending physician and assistant professor of medicine at New York University. Ofri’s collection of essays is essential to the medico-literary narrative for its ethical depth, particularly her courageous meditations on suicide and abortion. Claude Bernard, the great French clinician, wrote in 1865, “I am convinced that when physiology is sufficiently far advanced, the poet, the philosopher, and the physiologist will all understand each other.†Ofri is the fulfillment of his prophecy.

In “Living Will,†a patient asks what reason he has to live in the face of failing health, a dismal marriage, and chronic depression. Ofri struggles to reply, and despite her perfunctory attempts (try painting, get a dog) she feels the weight of his desperation. “If I were Mr. Reston,†she writes, “I might have pulled that trigger.†Her empathic instinct seems inborn. Ofri’s voice has the unifying power that Margaret Fuller sought; in fact, Incidental Findings is the medical version of Fuller’s notion that “every relation, every gradation of nature is incalculably precious, but only to the soul which is poised upon itself, and to whom no loss, no change, can bring dull discord, for it is in harmony with the central soul.†As a healer, Ofri searches for signals of hope in her most disconsolate patients—the “creak of the castle door,†as she puts it—without pretending to have quarantined despair. Her gaze is reminiscent of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Joan Bascom, who observes her patients “first professionally, then with a deeper human interest,†searching for stories where the clinical gaze sees only symptoms. When Ofri discovers tattooed numbers on the underside of a patient’s arm, she realizes that Dora Millstein is a Holocaust survivor. Dora’s death prompts Ofri to re-imagine her hands as part of a “chain of touch†stretching back through years of caresses to the grip of Nazi soldiers. “These calloused bits of skin that I scrub daily,†she writes, “that I sheathe and unsheathe with airless latex gloves, […] may have been the last in this particular chain.†Such moments are memorable in Ofri’s essays because they reshape the medical stage. The patient is no longer parenthetical to disease; she plays the leading role, and the doctor becomes a supporting witness.

Ofri’s experience as a patient has taught her that nothing in or about the hospital is incidental. As a maternity patient too exhausted after delivery to reach the water near her bedside, she learns the dire importance of every kindness in the doctor-patient relationship: “When a nurse aide finally arrived and slid the pitcher the eight inches necessary for it to reach my desperate grip, I felt a swooning relief, a joy like that I’ve felt when I’ve done successful CPR on a patient and revived him from the dead.†Once she can summon the strength to stand, Ofri attempts a sponge bath. Her humiliation when the hospital staff will not respond to her calls for assistance in cleaning up the “bloody mess†is a powerful reversal of her usual status. Ofri’s struggle for dignity parallels the psychic transformation of the shaman, which begins with a prolonged illness that induces prophetic visions. A shaman must be broken before s/he can heal others, which is precisely what happens in Ofri’s narratives.

In “Common Ground,†which also appeared in Best American Science Writing 2003, Ofri recounts her temporary position at a Catholic medical center that refuses to offer birth control and explicitly forbids referrals to abortion clinics. When one of her patients faces an unwanted pregnancy, Ofri decides that her ethical obligation to provide needed care trumps the hospital’s rules. She is shocked to learn that her patient’s insurance company will only cover abortions out of state. “I felt like we were back in the 1950s,†she writes, “sneaking around with code words.†She recalls the bleak exile of the abortion clinic she visited during her first year in college, the social strictures that have kept this story hidden for so many years, and her recognition that she may have died without safe access to the clinic. The sentences grow shorter, like breaths, as the essay approaches her memory of that day:

As the car shuffled closer and closer to the clinic, I felt my body shrinking. It dwindled within itself until there was nothing left but a little girl who desperately wanted her dog. […] I didn’t want to know. I didn’t want to remember.

I awoke crying in another room. […] My stomach pulsed with an alien ache.

Confessional prose is not much en vogue at the moment, but Ofri’s confessions are charged with politico-cultural force. She must consistently shake herself out of professional discourse into the realm of emotion, where doctor and patient are alike. “It is humbling,†she writes, “to know that we are all made of the same stuff.†Ofri’s essays are nearly all meditations in humility. Given what Atul Gawande has styled as “medicine’s twenty-first century, tall-in-the-saddle confidence,†her book is a cultural miracle. Reading Ofri is like watching a U.S. Marine weep.

The most dominant metaphor in modern medicine is war—the physician and the disease locked in an epic struggle. Ofri resists the war metaphor, and her purpose as an essayist is to foreground the patient in his/her own drama of health and illness. One of her patients discovers that he has diabetic neuropathy, a chronic disease that inflames the nerves in his feet and causes him to recoil from the slightest touch. Mr. McCreary is a prison inmate who has managed to remain ignorant of his diabetic condition until mid-life. The onset of neuropathy, however, marks a permanent shift in his narrative of health, “just the first step along that yellow-brick road toward lifelong hemodialysis.†Ofri imagines McCreary’s discovery as a tragic emigration “from the land of insouciant good health over to the land of disease with a one-way ticket.†She lingers with McCreary in the prison ward, gazing out at the East River through the wire mesh that covers the windows, and for a moment we are all incarcerated in nascent disease. Ofri transforms the most incidental of patients, a middle-aged prisoner, into a figure of our collective vulnerability.

We recognize these reversals as old literary patterns—Shakespeare’s subversion of primogeniture, the rise of the foundling in Dickens, the deconstruction of race and class in Twain—yet they resonate in Ofri’s essays because we understand that she is preparing for her own death and calling on us to do the same. Each patient represents her potential fate and ours. Each essay in Incidental Findings strips away the prophylactic gloves that the healthy stretch over their minds. Ofri drags us into the medical narrative as the man in Plato’s allegory is carried reluctantly from his cave, and in this she satisfies Emerson’s credentials for the poet as “the true and only doctor; [who] knows and tells.â€