Patients Need Poetry…And So Do Doctors

by Danielle Ofri

Slate Magazine

Rafael Campo, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard, just won a major international prize. It wasn’t for his excellence in internal medicine, or his decades of teaching, or his scholarship. It was for a poem.

A poem?

Poetry often seems the least practical endeavor on Earth. It’s a smattering of words on the page, often with minimal form, story, or logic. It doesn’t earn money, build cities, cure illness, feed the hungry, or solve the pressing problems of society.

But sometimes it is the things we deem least practical that wield the most power. In fact, poetry’s impracticality may be its strength. By being just words on a page, it isn’t expected to pull the weight of chemotherapy, antibiotics, or an MRI machine. So when a poem does pack a punch, we’re often bowled over.

“When we read or hear a poem that’s truly effective,†says Campo, “we feel what the speaker is feeling. We experience an entire immersion of ourselves in another’s consciousness.â€

For those of us faced with the challenging task of teaching—or preserving—empathy with the next generation of doctors, this experiential definition of empathy nails it in a way that no PowerPoint lecture could. Given our knowledge about such experience is crucial.

How does one teach, for example, how to face death? Death, dying, dead bodies—not easy concepts for anyone to contemplate, but they are a reality in medicine, and doctors and nurses will face them in their cold, hard actuality. Where do we gain the fortitude to step into the same space as death and negotiate the unnerving complexities that eddy between our breaths? It’s not the type of thing you can Google …

Forgive me, body before me, for this.

Forgive me for my bumbling hands, unschooled

in how to touch: I meant to understand

what fever was, not love. Forgive me for

my stare, but when I look at you, I see

myself laid bare ….

So opens Campo’s prize-winning poem, Morbidity and Mortality Rounds. It’s an immersion into the maw of death. I’ve read textbooks and articles about facing death, but they don’t capture the essence of the experience the way these few lines do. Every doctor and nurse will recognize “when I look at you, I see myself laid bare.†It’s the fierce existential tie between caregiver and patient.

For patients, who can find themselves lost and voiceless in the overpowering medical enterprise, poetry can often help recapture their voice. Campo, who also teaches writing at Lesley University, frequently distributes poems to his patients—it’s just one more tool for him in the toolkit of medicine. (Here’s with one of our homeless, alcoholic patients at Bellevue—the type of patient who is easily marginalized.)

Poetry and humanities are beginning to flower in the medical world. Many medical schools, such as , are devoting resources and time toward the humanities. Journals such as the Bellevue Literary Review (for which I’m the editor-in-chief) focus on creative interpretations of medical challenges and vulnerabilities. It is increasingly apparent that doctors and nurses need the creative skills that the humanities offer to be effective and wise caregivers.

Campo’s newest book of poetry, , will be published this fall. “A good poem engulfs us,†says Campo, “takes hold of us physically. Its concision and urgency demand the participation of another in order to achieve completeness, to attain full meaning. In these ways, it’s not so different from providing the best, most compassionate care to our patients.â€

Good medicine indeed! (from Slate Magazine)

**********

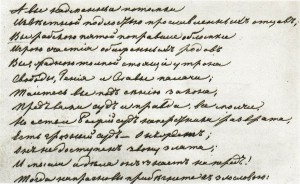

Morbidity and Mortality Rounds

By Rafael Campo (reprinted with permission of author)

Forgive me, body before me, for this.

Forgive me for my bumbling hands, unschooled

in how to touch: I meant to understand

what fever was, not love. Forgive me for

my stare, but when I look at you, I see

myself laid bare. Forgive me, body, for

what seems like calculation when I take

a breath before I cut you with my knife,

because the cancer has to be removed.

Forgive me for not telling you, but I’m

no poet. Please forgive me, please. Forgive

my gloves, my callous greeting, my unease—

you must not realize I just met death

again. Forgive me if I say he looked

impatient. Please, forgive me my despair,

which once seemed more like recompense. Forgive

my greed, forgive me for not having more

to give you than this bitter pill. Forgive:

for this apology, too late, for those

like me whose crimes might seem innocuous

and yet whose cruelty was obvious.

Forgive us for these sins. Forgive me, please,

for my confusing heart that sounds so much

like yours. Forgive me for the night, when I

sleep too, beside you under the same moon.

Forgive me for my dreams, for my rough knees,

for giving up too soon. Forgive me, please,

for losing you, unable to forgive.

(from Slate Magazine)