“Just tell me a story,” Dr. Danielle Ofri admonishes her medical students and interns at morning rounds. To Dr. Ofri, an attending physician at Bellevue Hospital Center, a part-time writer and the editor in chief of the Bellevue Literary Review, every patient’s history is a mystery story, a narrative that unfolds full of surprises, exposing the vulnerability at the human core.

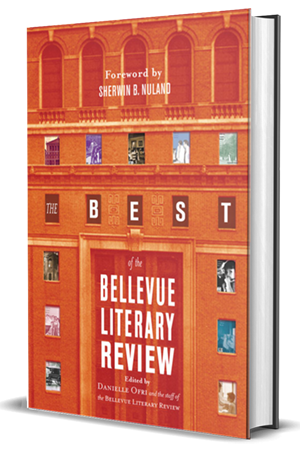

The review was founded two years ago by Dr. Ofri and Dr. Martin Blaser shortly after he became chairman of the department of medicine at the New York University School of Medicine, with which Bellevue is affiliated. The two created the journal to “touch upon relationships to the human body, illness, health and healing,” according to its mission statement, a broad canvas indeed.

Bellevue may be the only municipal hospital in the country to have a literary review. It has attracted well-known writers despite not paying its contributors. The review has published poems by Philip Levine, David Lehman and Sharon Olds, and this fall it is publishing its third issue, with poetry by Rick Moody, who is better known for his fiction. There is also a poem by Julia Alvarez called “Bellevue,” which reads, “My mother used to say that she’d end up/ at Bellevue if we didn’t all behave.”

Ms. Alvarez continues: “Of course, she wanted to go to Bellevue/ where the world was safe, the grates familiar,/ the howling not unlike her stifled sobs.”

Few contributions are by doctors. One, by Robert Oldshue of Boston, is his first published short story, “The Mona Lisa,” about a nursing home patient who is accidentally locked in an elevator overnight.

There is also an essay by Joan Kip, 84, on being widowed. “Alongside his love for me is my own expansive love for him,” Ms. Kip writes, “as we move in concert with one another across the illusion of separateness, embraced within a spiral of light, which has no beginning, no end.” Two pieces in the magazine are about ears. One, by Cortney Davis, a nurse practitioner, is a poem: “Pearly, uninformed, it waits/ for the otoscope’s puff of air.” The other is an essay by Eric Jones, a freelance science editor, about having an earache as a child. Dr. Blaser said he helped start the review to improve the medical students’ writing. “It became clear to me what poor writers most doctors are,” he said.

He has also instituted a new curriculum requirement at the hospital in which each student must write an essay about a patient. Like Dr. Blaser, Dr. Ofri said she was on a crusade to raise the level of medical students’ writing. Doctors speak and write as if “there are no people there,” she told her students on rounds. “Think of the way we give presentations. We say, ‘The spleen was palpated.’ Who palpated the spleen?”

“We say, ‘The patient admitted having a mammogram,” Dr. Ofri said. “Why are we so suspicious of our patients?”

Reading and writing literature, Dr. Ofri said in an interview, helps doctors “think more subtly, pay attention to the finer details, read between the lines, look for deeper meaning.”

Publication of Bellevue Literary Review is part of a national trend in medical education for schools to use literature to teach doctors how to write better and clearer case histories and to empathize more with patients. At Columbia University, the College of Physicians and Surgeons has a program in narrative medicine in which medical students read literary texts and compose essays and short stories to learn to write about patients in ordinary language.

The Bellevue Literary Review was started with $20,000 from the department of medicine at N.Y.U. Its unpaid staff consists of three doctors, Dr. Ofri; Jerome Lowenstein, a nephrologist; and Dr. Blaser, who is the publisher. It has 500 paid subscribers, not many even by the modest standards of literary magazines.

But it seems fitting that Bellevue Hospital, where writers have been committed in the extremes of mental collapse and which is at the center of American cultural life, would have a literary magazine. Malcolm Lowry set part of his novel “Lunar Caustic” in Bellevue after being committed to its psychiatric ward for observation. Part of Billy Wilder’s movie “The Lost Weekend,” which starred Ray Milland as an alcoholic, takes place at the hospital.

And among the writers who spent time as patients there are Norman Mailer, after he stabbed his wife, Adele, in 1960; William Burroughs, after he cut off his fingertip and gave it to a boyfriend; and the poet Delmore Schwartz, after he attacked the art critic Hilton Kramer, who he thought was having an affair with his wife. The playwright Eugene O’Neill and the poet Gregory Corso also spent time at Bellevue in stages of nervous breakdowns. The novelist Walker Percy was an intern there but left medicine after contracting tuberculosis.

Dr. Ofri emphasized that the magazine was not aimed just at doctors. “Everyone has been touched by illness,” she said. “Hopefully, it will illuminate something for them.” The review is sold nationally by Barnes & Noble and other bookstores.

“When you walk into Bellevue, there is humanity from all over the world,” said Dr. Ofri, who is 37, small and fine-boned and has a precise manner. She has published stories in The Missouri Review, the magazine Tikkun and other literary magazines and is writing a novel. In May the Beacon Press is scheduled to bring out a collection of her essays, “Singular Intimacies: Becoming a Doctor at Bellevue.”

“Just tell me a story,” Dr. Ofri tells her students again and again. “Don’t just read from your notes.”

On rounds recently Dr. Ofri and her students discussed a Tibetan monk who had been referred by the Bellevue/N.Y.U. Program for Survivors of Torture. After demonstrating for Tibetan independence, he was tortured by the Chinese. The monk was also a hemophiliac, and his legs were deformed by internal bleeding.

“What is the social history?” Dr. Ofri asked the medical students standing around the patient. “The social history is important. If a patient lives on the street, and you send them out with dressings that need to be changed, that is a problem.” The monk, it turned out, was staying with a group of Tibetans in Queens.

At the end of rounds Dr. Ofri often makes her tired students listen to a poem or an essay. “Sometimes it requires chocolate to make them stay,” she said.

A recent poem was “Gaudeamus Igitur” (“Let Us Rejoice Therefore”) by John Stone, a doctor and writer, first delivered as a valedictory address at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta. It was inspired by the medieval song of that name, and its form, in which every line begins with “for,” was suggested by “Jubilate Agno” (”Rejoice in the Lamb”), written by the 18th-century poet Christopher Smart in praise of his cat.

“For this is the day you know too little,” Dr. Ofri read, “against the day when you will know too much/ For you will be invincible/ and vulnerable in the same breath/ which is the breath of your patients.”

She continued: “For there will be addictions: whiskey, tobacco, love/ For they will be difficult to cure/ For you yourself will pass the kidney stone of pain.”

The poem ended: “For there will be days of joy/ For there will be elevators of elation/ and you will walk triumphantly/ in purest joy/ along the halls of the hospital/ and say Yes to all the dark corners/ where no one is listening.”