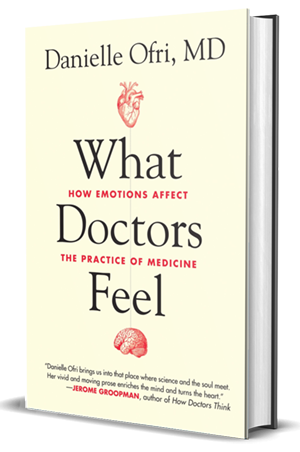

New York Times review of “What Doctors Freel”

by Katie Hafner

New York Times

In her new book, What Doctors Feel, Dr. Danielle Ofri tells the unforgettable story of a pediatrician she interviewed, a woman she calls Eva.

In taut, vivid prose, Dr. Ofri describes a tragic event that occurred during Eva’s residency. She helped deliver a baby doomed to asphyxiation within minutes of birth because of a severe lack of amniotic fluid in the womb.

The traumatized parents knew the outcome in advance, and made it clear they did not want to see the baby. After the delivery, the room leaden with silence, Eva wrapped the baby in a blanket and wondered where to go. The hospital had no room set aside for this. So the young physician, consumed with sadness for a child who would never be held by anyone but her, took the dying newborn into a supply closet.

There, knowing she would be reprimanded for not observing the precise moment at which the umbilical cord ceased pulsing, she gathered the baby in her arms. “In the cramped space Eva rocked back and forth,” Dr. Ofri writes. “ ‘I love you, baby,’ she whispered as the heart began its slow, cratering descent.”

In the hands of a less agile and intelligent writer, such a scene could easily grow maudlin. Indeed, calling attention to a physician’s emotional pain might be seen as distracting and self-indulgent. It is, after all, the physician’s role to ease the suffering of others.

Yet as Dr. Ofri points out, how doctors feel matters. And while she does write of joy, pride and gratitude, her emphasis is on negative emotions — which exert the strongest influence on medical care, particularly when a case grows unexpectedly complicated, frustrating or unyielding. “This is where factors other than clinical competency come into play,” she writes. An unwell doctor is a bad doctor.

Dr. Ofri is an internist at Bellevue Hospital Center in New York City, which cares for legions of indigent, uninsured patients, as well as a large population of immigrants. The author of three previous books and a frequent contributor to The New York Times, she writes for a lay audience with a practiced hand.

This book’s hallmark is her honesty, particularly when it comes to the emotional fallout of her medical mistakes. When she dismisses a patient’s litany of vague symptoms as stress-related, only to miss a blood clot in each lung, she is overwhelmed by shame and remorse.

She is also frank about her prejudices, particularly toward the worried well. Early in her career, during a summer job at a tony practice on Long Island, Dr. Ofri refused a woman’s request for weight-loss pills. “After three years of round-the-clock AIDS, cancer, congestive heart failure and cirrhosis, it was hard to get worked up over a couple of middle-aged pounds,” she writes.

But later she rethinks her reaction. “I wasn’t able to step past my own issues,” she writes. “Maybe underneath the seemingly superficial concerns were serious issues that were crying out for attention.”

Then there is the constant thrum of death: Eva and the dying newborn; a young patient under Dr. Ofri’s care with heart disease whose stormy course appears to end with a successful heart transplant, only to be followed by a fatal stroke.

It does make one wonder how doctors cope. A study of oncologists cited by Dr. Ofri found that these specialists learned to compartmentalize their grief. Yet the most striking finding of the study was how poorly that strategy worked. Grief spilled into the physicians’ daily lives and sapped them of their inner strength.

After the newborn’s death, Eva walled herself off from all emotions, only to have them return many months later with full-blown post-traumatic stress disorder.

Bitterness is here, too. Dr. Ofri devotes much of one chapter to malpractice lawsuits. She describes her own harrowing experiences of being sued — in one instance, by the family of a woman she had not just grown close to, but gone well out of her way to care for. “Dealing with a lawsuit is often likened to having a death in the family,” she writes. “Doctors end up (often unconsciously) grieving for the doctors they used to be.”

Counterintuitively, perhaps, Dr. Ofri is at her most compelling when telling other physicians’ stories. It’s almost as if she still needs to keep a slight cool distance from her own experiences. But this is not necessarily a sign of weak writing. It is an indication of just how raw the inner life of a doctor can be.