JAMA review of “Singular Intimacies”

by Jason Chao

JAMA

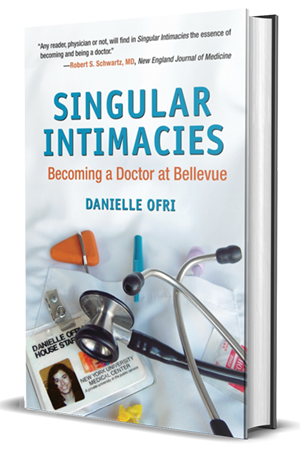

This book is a collection of short, autobiographical chapters about being a doctor-in-training, from the first day on the wards as a third-year student through the final months of residency, with a more recent prologue and epilogue as bookends. The author, Dr Danielle Ofri, is currently assistant professor of medicine at New York University and attending physician at Bellevue Hospital. She is also editor-in-chief of The Bellevue Literary Review, the first literary magazine based in a hospital. In Singular Intimacies Ofri chronicles her training in an adept and touching manner. Although each chapter is fairly self-contained and could almost stand alone, occasional references to events in previous chapters tie the book together.

For a medical student and resident in New York City in the early 1990s, HIV infection was commonly encountered. In that era before effective medications were developed for treating AIDS, the diagnosis was a sentence of death within months to years, not decades as it is now. Several chapters of Singular Intimacies deal with the virus. An early chapter describes the author’s terror when she suffers a needle-stick injury while scrubbed in during an operation in the middle of the night. The longest chapter describes caring for a cachectic young woman who is in denial of her illness. The rest of the medical staff are also in denial, looking for any other diagnosis besides HIV.

Ofri is an accomplished writer. Her prose contains brief but intricate descriptions of everyday situations and locations in and around the hospital. She describes the operating room,where the surgeon uses cautery to stop excess bleeding:

. . . that pungent cloying smell has never failed to paralyze my senses. Burning skin. Crisping meat. Human sacrifice. Is that how Dachau smelled?

The edges divided, unearthing more flesh—the pink richness of muscle and the oily gold of fat.

And here is her description of one of her patients with AIDS:

Her teeth seemed enormous, but that was only because the rest of her face had receded so. The flesh had ebbed back, shrinking from contoured fullness to spare, arid outlines. Fragile porcelain skin lay draped over the angular bones, like sheets over spindly furniture. Translucent freckles dotted the landscape, but weren’t enough to impart color. Her hair was brittle and red, with furtive spots of scalp peering through. In places, the amber hues had faded to a waxen yellow. But her eyes were blue, disarmingly blue, the heavy ocean blue of youthful eyes—eyes not old enough for cataracts or glaucoma to cloud them.

Themes that resonate include the frustrations of a doctor in training; the hierarchy from lowly third-year medical student through intern and resident to lofty attending physician; the observation of medical decisions by attendings that appear suboptimal;and the medical errors and mysteries that persist despite all the high tech of modern medicine. Ofri struggles with the meaning of life and death through a patient who emerges from cardiac resuscitation in a vegetative state.

Two stories involve physicians as patients—one with terminal cancer who continues with medical interventions that lead to eventual fatal complications, the other a subspecialist attending known for his intelligence and wit who commits suicide. Ofri mentions the cliché that “doctors make the worst patients”and wonders about their denial of their own illnesses: “[I]s that the Faustian bargain we make when we enter the professions? I don’t want to believe that is true, but for some it is apparently so.”

Most of us have memorable first patients from our training years: the first patient who called us Doctor; the first patient we successfully cured, treated, or delivered; the first patient who died on our watch. Ofri recounts some of her firsts: her first patient as a beginning third-year student; the first patient she drew blood from; the first patient who considered her to be his doctor; the first patient she actually hated because of his meanness. These firsts triggered thoughts of my own firsts, good and bad.

Ofri’s personal story comes out in bits and pieces through the various chapters. She grew up in New York and is Jewish. She took a less common path, completing a PhD in biochemistry between her second and third years of medical school. A close friend died of sudden cardiac arrest when Ofri was an intern,a devastating event that causes her to reflect on the power and limits of medicine.

The prologue describes a patient recently in the author’s care as attending physician. The patient has lung cancer and is in acute respiratory distress. She states that she wishes to be intubated no more than 7 days and, if she dies, to be buried in France. In the epilogue, we return to the patient, who has been extubated, seven days later. Before giving the patient’s outcome, the author summarizes her own life after residency, including co-founding The Bellevue Literary Review.

I found Singular Intimacies extremely engaging. It contains an accurate portrayal of life as a doctor-in-training in a big city hospital. I highly recommend it to anyone who wants an easy-to-read yet thought-provoking book.