Even with lawsuits and co-pay caps, will Insulin ever be affordable?

By Danielle Ofri

Stat News

In an attempt to tackle the root causes of the inflated cost of insulin, the state of California filed a lawsuit last week accusing drug manufacturers and pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) of artificially and illegally jacking up the price of insulin.

The sausage-making of how insulin is priced is not for the faint of heart. It’s a complex tangle of drug manufacturers who’ve been resisting generics, health insurance companies trying to keep up impressive profits, plus the wholesalers who distribute medicines to pharmacies and the pharmacies that provide them to patients. Slithered into this midst are the pharmacy benefit managers, companies that negotiate the prices for medications on behalf of insurance companies and administer the prescription drug aspect of individuals’ health insurance.

The cost of insulin begins with the list price, which is set by the companies that make it. Three manufacturers dominate the global insulin market: U.S.-based Eli Lilly, Denmark-based Novo Nordisk, and France-based Sanofi. Insulin falls into the category of biologics—medicines produced from living organisms like yeast and bacteria, or derived from living cells and tissues. These are more complex and expensive to produce than so-called small-molecule medicines like aspirin and furosemide that are synthesized via standard chemistry protocols.

Drug companies routinely justify that their high prices are due to complex manufacturing process. These claims have been debunked, including by a recent study that directly compares what drug companies spend on drug development to how they price their products and found no relationship at all.

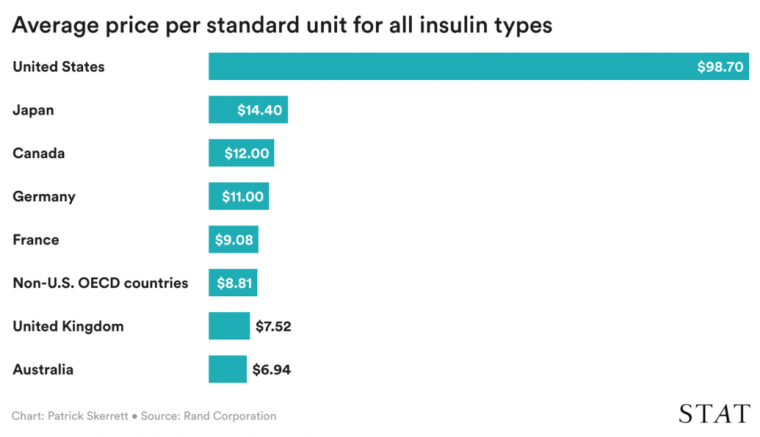

The truth is that drug manufacturers can set their prices as high as they want in the U.S. because there is absolutely nothing that prevents them from doing so. These companies sell the identical products to other counties for shockingly lower costs. In a graph that will drive your sugar up even if you don’t have diabetes, researchers with the Rand Corporation showed that Americans with diabetes pay up to 10 times more than their international peers for the same insulin products.

Under the standard rules of capitalism, the three main manufacturers of insulin would be expected to compete and push prices down. But the companies actually “price-shadow” their products, raising prices in unison.

Pharmacy benefit managers play a unique and somewhat cryptic role in the cost of insulin. PBMs initially started out doing a specific task: handling the nitty gritty of processing and adjudicating prescription claims that insurance companies and large employers were only too eager to farm out. Their remit has expanded and they now create the formularies that dictate which medications an individual’s insurance will cover.

Although their job is to negotiate drug prices for these formularies on behalf of insurance companies—and thus for patients—a hefty chunk of the savings they extract from drug makers ends up in their own pockets and is not passed on to the insurance companies or their customers. Even when lower-priced biosimilar insulins became available in 2021, most PBMs chose higher-priced branded versions for their formularies. Because their fees are usually a percentage of the list price, they have every incentive to select higher-priced medications. They could negotiate “discounts” and “rebates” off these higher prices, but they would still pocket larger fees established by the original high price.

Aggressive mergers and consolidations have whittled the PBM field down to three main players—CVS Caremark, OptumRx, and ExpressScripts—who together control more than three-quarters of all prescriptions in the U.S., so there is little competition. (And in a spectacular example of vertical integration, these PBMs are now owned by health insurance companies: CVS Caremark by CVS Health, which also owns Aetna health insurance as well as the CVS drugstore chain, OptumRx by United Healthcare, and Express Scripts by Cigna.)

The Inflation Reduction Act that is going into effect this month made news as the first federal legislation to address insulin costs. But when the dust settled, it turned out to be even less than a Band-Aid, helping only a small fraction of people needing insulin by tackling only a small fraction of the problem.

Let’s start with the small fraction of patients. In the original bill, the cap applied to everyone using insulin. Due to opposition from Senate Republicans, however, the final bill stripped most beneficiaries out of this provision, so it now applies only to the 18% of Americans with Medicare. The other 82%—people under 65, anyone with regular insurance, and those who lack insurance—remain at the mercy of market forces for insulin.

The second issue is that the act tackled only a fraction of the problem. The cap applies to the co-pay on insulin—the portion that patient contributes—not the actual list price of insulin. A $35 cap on the co-pay no doubt offers tangible relief for some people, but it papers over the mess that has led to the jaw-dropping prices of insulin. To be fair, Senate Republicans did make this point in their objection to the co-pay caps, though they did not offer any alternative solutions. The fact that drug companies are lobbying in support of these caps on co-pays as a solution to the crisis should be an immediate red flag.

I’m a physician, not an economist. But the diagnosis seems plain as day: greed. America has decided that health care — unlike our water supply, education, the roads we drive on, and so much more — is not a fundamental right of its people. Once we’ve allowed health care to be an economic entity like mobile phones, sports cars, and jewelry, all players with fingers in the pie will extract as much money from the process as the market will bear. Insulin is the poster-child for this uniquely American rapacity, though is certainly not the only example.

A disturbing new study recently revealed that 20% of Americans with diabetes have rationed their insulin—cutting or skipping doses, or doing without—because of financial reasons. Insulin upheaval is so common that there are now algorithms for doctors to use when their patients can no longer afford their prescribed insulin.

California’s attorney general named in the state’s lawsuit all three of the major insulin manufacturers and all three of the largest PBMs, accusing these six companies of hiking prices far beyond inflation and the cost of development. In particular, the suit targets the lock-step increases in list price by the manufacturers, the opaque price negotiations by the PBMs, and the “oligopolistic” nature of the entire enterprise that ultimately benefits corporate entities rather than the people who use insulin.

The headlines generated by the Inflation Reduction Act’s insulin co-pay cap gave many people the impression that Congress had done its job to control insulin costs. But that is hardly the case. The $350-million-dollar lobbying efforts of the pharmaceutical and health care industry may offer some hints as to why Congressional efforts have been so tepid.

Despite a deeply divided government, however, controlling medication prices is a bipartisan issue for both voters and politicians. Plenty of other countries have managed to maintain healthy capitalist economies while still enacting laws to regulate health care costs. Admittedly, having universal health care systems helps, but there’s still plenty that Congress could do. It could pass regulations forbidding drug companies to charge Americans 10-fold more for insulin than they charge people in other countries. It could investigate the black box of PBM negotiations and regulate the anti-competitive practices that are rampant in the pharmaceutical industry. It could allow Medicare to use its buying power to negotiate drug prices for all medications, not just the handful in the Inflation Reduction Act. And it could regulate the abuse of the patent system that locks in monopolies and discourages generics. Congress just needs the guts to put patients before lobbyists.

At the moment, the legal system may be the only route to address the current spate of insulin price gouging. California’s lawsuit follows on the heels of similar actions from Illinois, Arkansas, Mississippi, and Kansas. Plodding state by state will not bring the urgent relief that people with diabetes need, but the courts may offer the only hope to achieve what Congress lacks the courage to do.