Empathy in the Age of the EMR

by Danielle Ofri

The Lancet

In 1891, the English artist Sir Luke Fildes painted what is considered to be the iconic portrait of a physician. I”The Doctor,” a Victorian GP in formal black attire is seated at the bedside of a sick child, staring pensively at the young girl. The family huddles in the background awaiting the doctor’s determination.

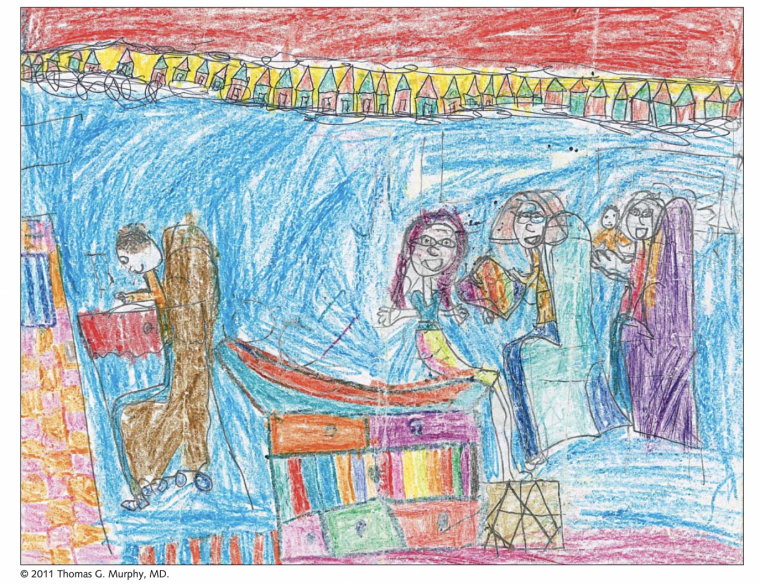

Almost 130 years later, a seven-year-old girl handed her pediatrician a what might be considered a 21st century remake of Fildes’ painting. Done with crayons rather than oils, this picture is iconic nevertheless. The child is on the exam table, with family behind her, and they are also awaiting the doctor’s determination.

Although there is much dated paternalism in Fildes’ depiction, what stands out—and stands the test of time—is the focus of the doctor that is directly, wholly, and steadfastly on the patient. The contrasting scenario of today, pithily illustrated by the young artist with her crayons, is of the doctor marooned on stage left, tending to what is obviously the most important medical element in the room—the computer.

I think about these two works of art often during my clinic sessions these days. Like all of my colleagues, I desperately desire the luxury of focus that Fildes’ doctor enjoys, but reality forces me into the latter-day depiction—hunched over a terminal, squinting at a screen, enslaved to the electronic medical record (EMR), abjectly clicking until my carpal tunnel disintegrates into collagenous pudding.

Keeping the doctor-patient connection from eroding in the age of the EMR is an uphill battle. We all know that the eye contact that Fildes depicts is a critical ingredient for communication and connection, but when the computer screen is so demanding of focus that the patient becomes a distraction, even an impediment—this is hopelessly elusive.

Recently, I was battling the EMR during a visit with a patient who had particularly complicated medical conditions. We hadn’t seen each other in more than a year, so there was much to catch up on. Each time she raised an issue, I turned to the computer to complete the requisite documentation for that concern. In that pause, however, my patient intuited a natural turn of conversation. Thinking that it was now her turn to talk, she would bring up the next thing on her mind. But of course I wasn’t finished with the last thing, so I would say, “Would you mind holding that thought for a second? I just need to finish this one thing.”

I’d turn back to the computer and fall silent to finish documenting. After a polite minute, she would apparently sense that it was again her turn in the conversation and thus begin her next thought. I was torn because I didn’t want to stop her in her tracks, but we’ve been so admonished about the risks inherent in distracted multitasking that I wanted to focus fully on the thought I was entering into the computer. I know it’s rude to cut someone off, but preserving a clinical train of thought is crucial for avoiding medical error.

My other reason for holding her off was to prevent my clinical train of thought from interrupting her story. We doctors are (rightfully) entreated to be mindful with our patients, to be fully present and attuned when they are speaking. It’s a matter of human respect, but it’s also integral for minimizing diagnostic error. Catching the subtleties of the medical history is how we increase diagnostic accuracy and avoid the sloppiness of all-you-can-order medical testing. The only way to listen fully to her was to have her wait until I completed my clinical thought.

“Just give me a minute,” I’d beg of her, typing maniacally to catch up.

And so it went, as we plowed through her nearly two dozen medications, her many visits to specialists, her labs, her CT scans, and recent illnesses. At every step of the way, as she brought up each of her concerns, I found myself uttering some variation of, “Hold on,” “Just a sec,” “Can you give me another 20 seconds?” “Sorry, don’t meant to cut you off, but…”

By the rules of normal conversation, cutting someone off is rude. Even if my holding her off was actually a manifestation of trying to be a good listener, it still felt boorish.

Trying to respect the dictums of avoiding multitasking and also fully focusing on listening put me in an impossible bind. I could, of course, fake it—listen with half an ear while corralling the rest of my intellectual vigor on the 6743 fields that need to be clicked in precisely the right order to placate the EMR in all its oracular glory.

Many of us physicians muddle through our clinical encounters in this manner. We’re half-listening, half-typing, half-processing what tests we’ll need to order, half-chiding ourselves about an oversight from our last patient, half-ignoring the red-flag alerts that keep cropping up, half-thinking about the next three patients in the waiting room, and half-pondering whether one of the EMR buttons could do something practical like conjure up a cup of coffee and a sandwich.

The only thing that’s not diminished by half is the feeling that we’re cutting corners on every front and scraping by with mediocre medical care.

So where does that leave empathy in the age of the EMR? In the Fildes painting, the empathy of the doctor is palpable. It embodies the reasons most of us entered medicine. The modern crayon reincarnation of the painting embodies our fears, that we will be reduced to tools of mere data entry. A higher being might peek into our exam room and be unable to distinguish the doctor from the sphygmomanometer.

The connection between doctor and patient is the foundation of empathy. How can we even begin to sense our patients’ world if we are hardly glancing in their direction, listening with only half an ear, or cutting them off every time they try to talk because we ourselves are drowning in the EMR?

I wish I had an easy answer. We’ve been promised that artificial intelligence will elevate us to a higher plane, removing much of the drudgery and allowing doctors and patients to focus on the stuff that matters. These advances in AI offer me a sliver of hope that perhaps someday the EMR will be able to intuit my clinical reasoning for my patient’s renal tubular acidosis and ankylosing spondylitis, thus leaving the patient and me wholly emancipated for in-depth history, physical, and co-pondering of the universe. But for the moment I’m stuck shackled to the keyboard, pecking away in attempt to compose a semblance of rational thought while the patient is sixteen steps ahead on her review-of-systems.

There is at least one upside to this mess, however. The aggressiveness of the EMR’s incursion into the doctor-patient relationship has forced us to declare our loyalties: are we taking care of patients or are we taking care of the EMR?

Reminding ourselves of the answer to that question can help set the priorities straight. It doesn’t diminish our workload in the moment, but it can at least keep our compasses pointed resolutely northward. When I start a visit now, I try my best to commit the first minute to talking directly with the patient, conspicuously elbowing the computer screen out of our interaction.

Then, as I embark on the documentation gauntlet, I endeavor to involve the patient in each step (“Okay, let’s do that losartan prescription now.”) This at least avoids the deadly silences during which while I mouth unprintables at the screen and my patient tactfully contemplates the supply cabinet. These can even be moments of clinical education and reinforcement. (“You are taking 100 mg, right? Are you having any trouble with this medication?”)

And when there’s a moment that I think needs full-frontal listening but the patient is several steps ahead of me, I try something specific like: “I don’t want to make any mistakes in ordering your ultrasound, so hold that thought for one second.” And when I’m done, I extricate my eyes and body from the screen so that we can have a real conversation.

Empathy doesn’t require us to address and solve every problem. Our patients understand the time constraints and the EMR frustrations, and are largely sympathetic to our plight. But empathy does require attention to connection. The EMR forces us to invest conscious effort into being present.

Humor can be a helpful leavener. There’s no shortage of my own tech bumbles that I can poke fun at, though the EMR often offers levity on its own. With one patient, the EMR flashed a notice, cheerfully reminding us that his tetanus shot was “next due” in September, 1955.

My other strategy is to keep a box of crayons at the ready. Whenever a patient arrives with children in tow, I immediately set up the supplies on my exam table and task the kids with decorating my desolate gray walls. My main goal is to keep them occupied while I talk with the parent, but I keep my eye on the artworks-in-progress. You never know when the next Fildes will arise.