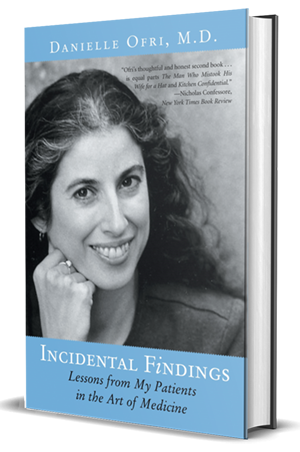

JAMA review of “Incidental Findings”

by Jason Chao

JAMA

This is Danielle Ofri’s second book of short autobiographical stories. Following Singular Intimacies, which recounted her medical training as a student and resident, this new volume draws on her experiences as a practicing physician. Similarly, it consists of a series of fairly self-contained chapters, although later chapters make occasional reference to people or events from previous chapters, providing some continuity through the book.

The first few chapters describe some of her encounters just after residency while doing locum tenens work in Florida, New England, and New Mexico. The remainder of the episodes take place at Bellevue Hospital, in New York City, where Ofri now works as an attending physician in general internal medicine. She is also founder and editor-in-chief of the Bellevue Literary Review.

As the subtitle suggests, Ofri learns much from her patients as she attempts to help them. Many have significant medical illnesses, and depression is a common comorbid condition. Ofri explores her patients’ feelings and strives to understand each as a person. She also opens up with her own doubts and questions. For instance, she describes her feelings as she sees a frequent patient who has endless complaints:

The feeling begins: a dull cringing in my stomach that gradually creeps outward, until my entire body is sapped by foreboding and dread. I feel myself slipping into her morass, and the smothering sensation overcomes me. If she doesn’t stop, I will drown in her complaints.

Another author once coined the term “heart sink†for feelings evoked by such patients. But a sudden insight into her patient’s social situation provides Ofri with renewed energy to take a new approach and contract a therapeutic plan of action.

In several stories Ofri recounts her own experiences as a patient. She is surprised at how different things are on the other end of the doctor-patient relationship. The book begins as she and her husband wander lost, struggling to find the office of the obstetrician who will perform her amniocentesis. Ofri discovers firsthand how poorly doctors prepare their patients for procedures and explain findings that may be ordinary in medicine but are frightening to patients. In another chapter, she struggles with how much of herself to reveal to a patient, including her own abortion experience.

As an academic clinician in a busy urban teaching hospital, Ofri’s rotations covering the inpatient wards are overloaded. She rounds on a patient in denial of his diabetes who has painful neuropathy. She ends the visit with a promise to talk more with him the next day, but he is discharged too soon. In another case, Ofri’s resident prepares to discharge a patient with renal failure to hospice care, when the patient voices a desire to discontinue dialysis. In talking with the patient, Ofri determines that she is depressed and chronically ill, but not terminally ill. She convinces the patient that she should resume dialysis and reflects that she has saved a life but that the resident had missed an important lesson. In another story, Ofri laments the change to casual dress by house staff on noncall days, when a patient complains about the unprofessional appearance of residents.

I found the stories in this second book more disturbing than those in the first. Is it because the author is now an attending physician like me, and her challenges and difficulties are so similar to mine? The writing is engaging, and I highly recommend Incidental Findings to anyone who wants to read a short, well-written, and thought-provoking book.