UK Spectator: How to improve bedside manners

by Kate Womersley

The Spectator

‘A tricky part of my job,’ the GP said, scrolling through the next patient’s notes, ‘is breaking good news.’ As a medical student on placement, I listened as he told the young woman that her ‘presenting complaint’ —blurred vision, fatigue and tingling down her arms — was not in fact multiple sclerosis. The diagnosis had been made several years earlier but her latest MRI scan suggested that MS was very unlikely. Despite the GP’s prediction that this would be a complicated consultation, he still looked frustrated when the patient didn’t respond with relief to his diagnostic revision. Instead, her weariness was edged with anger. ‘If it’s not MS,’ she said, ‘why do I feel so unwell?’

For most doctors, ‘bad news’ means metastatic cancer, a paralysing stroke, amputation. For a patient, bad news might also include things like insomnia, taking pills for life, severe migraine. ‘To the typical physician, my illness is a routine incident in his rounds,’ said the American writer Anatole Broyard, ‘while for me it’s the crisis of my life.’ This different scale of suffering helps doctors triage with a cool head, but it can also lead to dispiriting clinical encounters. One might say the profession and the public do not always see eye to eye. Danielle Ofri argues in her new book that the problem is rather one of listening.

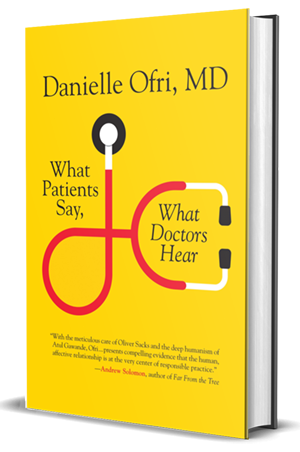

A physician of general medicine at Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan, Ofri is known for reading poems aloud on ward rounds. Her articles in the New York Times teach readers to appreciate patient stories as the most valuable currency in the unpredictable, imperfect business of healing. She is well aware that writing about medical mistakes, as in her book What Doctors Feel: How Emotions Affect the Practice of Medicine (2013), doesn’t enthuse all of her colleagues. Despite hospitals’ technological advances, Ofri insists that the ‘everything else’ of medicine — empathy, trust and a good bedside manner — although ‘notoriously difficult to quantify’, matter now as much as ever.

The ‘primary diagnostic tool’ for any medic is taking a good history, and like taking blood or taking swabs, the material for analysis should come from the patient herself. But doctors often undervalue the importance of staying silent, Ofri says — maybe because active listening is not a skill bestowed exclusively by completing a five-year degree. Ofri experiments with her own reluctance just to listen, and surreptitiously starts a timer in every consultation. She then lets her patients speak uninterrupted. The fear that they might never stop was misplaced: Ofri’s mean of 92 seconds doesn’t ruin her schedule, and pays dividends later. Yet studies show the average doctor interjects after just 12 seconds.

Certainly healthcare environments collude against attentiveness: the computer screen, the keyboard click, the translation of patient symptoms into codeable jargon (a doctor learns 10,000 new words during training), all intensified by the ten-minute countdown. Time-pressed juniors tend to dismiss patients as ‘poor historians’ if their narratives aren’t amenable to instant classification. But Ofri is adamant that meaning is ‘co-created’, and its elusiveness might be as much the clinician’s fault as the patient’s.

Central to diagnostic detective work, listening also has a therapeutic effect. Patients who feel acknowledged and unrushed report greater satisfaction, lower pain scores and better concordance to drug regimens (not to mention fewer errors and lawsuits for the doctor). This analgesic potential is welcome news to medical students who hang around the wards without the power to prescribe drugs, but do have time to sit and chat with the bed-bound. By listening carefully, doctors may then better use the salubrious effect of their own words to ‘frame things as optimistically as possible, within reason’. A well-chosen phrase, Ofri suggests, ‘may act physiologically by decreasing cortisol and adrenaline’, thereby altering the patient’s neural perception of pain. If there’s a choice not to reach for pharmaceuticals, ‘Conversation is way cheaper and it doesn’t decimate your sex drive or make you puke.’

Talking with patients — rather than at them — is a teachable skill. Like performing a lumbar puncture or reading a chest X-ray, it requires method and practice. Medical schools still select future doctors almost exclusively on academic excellence, yet have recently added Clinical Communication to their curricula. Few students look forward to being videotaped as they ask set-piece questions, stiff at first, to a medical actor. Acronyms such as ICE (‘what are the patient’s ideas, concerns and expectations?’) may seem forced, but it’s surprising how well they work, no matter if, as Ofri says, ‘your inner emotions haven’t quite caught up yet’.

Some will always see the doctor-patient exchange as a fluffy appendage to ‘real medicine’. But if Ofri’s book succeeds in easing the passage from ‘presenting complaint’ into open conversation, informative for and complementary to further technical interventions, that would be very good news for both the doctor and the patient.