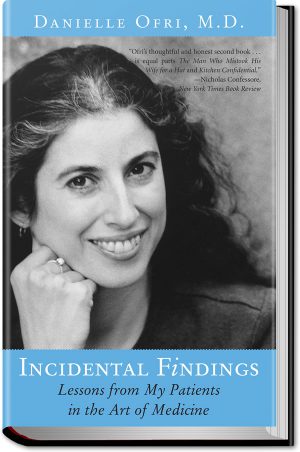

Torment

by Danielle Ofri

by Danielle Ofri

New England Journal of Medicine

(this essay later appeared in “Incidental Findings”)

I groan when I catch sight of her name on the patient roster. Nazma Uddin. Not again! She is in my clinic office almost every month. I dread her visits, and today is no exception. A small, plump woman, Ms. Uddin is cloaked in robe, headscarf, and veil, all opaque blue polyester. Only her eyes peer out from the sea of dark blue. She is trailed, as usual, by her 11-year-old daughter Azina, who wears a light green gown with a flowered headscarf pinned under her chin, but no veil covering her solemn, bespectacled face.

Ms. Uddin flops into the chair next to my desk, with a postural sprawl that is almost teenagerly. Azina perches on the exam table, her white Nikes peeking out from under the full-length gown. Ms. Uddin unsnaps her veil—something she does only with her female doctor—revealing her weathered cheeks, and the litany begins. “Oh, doctor,†she says, pinching the sides of her head with skin-paling force, “the pain is no good.†After this brief foray into English, she slips into Bengali, aiming her barrage of complaints at Azina, who translates them to me in spurts while fiddling with her wire-rim glasses. There is abdominal pain and headache, diarrhea and insomnia, back pain and aching arches, a rash and gas pains, itchy ears and a cough, no appetite. And more headache.

The feeling begins: a dull cringing in my stomach that gradually creeps outward, until my entire body is sapped by foreboding and dread. I feel myself slipping into her morass, and the smothering sensation overcomes me. If she doesn’t stop, I will drown in her complaints.

I begin to filter.

I fight it, but it is impossible. I know that I should be focused on Ms.Uddin’s words, but I fear for my sanity and my ability to get through this visit and move on to the next 10 patients. I begin to ignore a certain percentage of what is being said, nodding vaguely, murmuring off-handedly—shortcuts to suggest that I am engaged but are merely smokescreens to keep her at bay. I scan the computer while she moans about her shins and her coccyx, and I see that she has been to Neurology Clinic, Rehab Clinic, Pain Management Clinic, Gynecology Clinic, Podiatry Clinic, GI Clinic…all in the five weeks since I last saw her.

“Doctor,†she is pleading with me, now in English, and I hurriedly refocus on her. “Why so much pain?†The leathery grain of Ms. Uddin’s skin and her seemingly permanent submersion in the world of the sick make me think of her as elderly. I am always shocked when the computer reminds me that she is 35. “Why, doctor, why?†Her laments are punctuated by the resonant thud of Azina’s sneakers banging repetitively and absentmindedly against the metal exam table.

When not translating, Azina gazes at the posters in my office—cheap, miniature, museum prints of Monet, Wyeth, and Hockney that are nonetheless bolted to the wall to prevent theft. Her eyes drift over to my desk, with its piles of papers, journals, memos, and prescriptions. Our eyes accidentally meet, but her expression is mute and mine is likely frustrated. Azina turns quickly away and begins fingering the crinkly white paper covering the exam table.

I desperately want to get Ms. Uddin out of my office. I hate my visits with her, and it is increasingly difficult to mask that. Like all the other doctors who see Ms. Uddin, I’m anxious to write a few more referrals or a few more prescriptions just to get her out of my hair.

The truth is I can’t do anything for Ms. Uddin. I’ve talked to her endlessly about stress and depression, which I am sure underlie many of her pains, but she never follows through with the psychiatry referrals or antidepressant prescriptions. Her resistance to my efforts sometimes makes me feel as though she is in a personal battle against me.

I start to resent her, to hate her, to hate everything about her. I hate to see her name on the roster. I hate to see her in the waiting room. I hate the whine that in her voice, that is detectable even when she is speaking Bengali. I hate that she keeps her daughter out of school to facilitate her wild overuse of the medical system.

And I hate how she makes me feel so utterly useless.

Whenever I’ve tried to treat one complaint, another bursts to the surface like a mocking hydra: An antacid temporarily relieves her stomach pains, but then she will have palpitations. A migraine medication partially assuages her headache, but then she will have intractable hiccups and swollen knees.

I can’t breathe, she says. I don’t eat. I don’t sleep.

Well if that’s truly the case, I want to retort, how is it that you are still alive?

I stop listening to what she says. I stop believing what she tells me about her symptoms. Stop it, I want to yell to her. Just stop complaining. Go away. Stop bothering me. You know and I know that this is hopeless.

I shudder as I realize that I am slipping too far. The annoyance and resentment are getting the better of me. I wish she would just disappear—out of my office, out of my hospital, out of this city, off this planet. How is it that she emigrated thousands of miles from her obscure village in Bangladesh to end up precisely in the catchment area of my clinic, and then randomly in my office out of the hundred and fifty other medical attendings and residents?

Why, I plead with myself, can’t I unearth some grain of humanity? Why can’t I put my feelings aside to help a patient in need, no matter how annoying?

Back at our first visit—if I can even remember that far—I was probably compassionate. I’m sure I asked open-ended questions, and responded with concern to each of her problems.

Now I am the model of the curt, hyper-efficient doctor. I ask as few questions as possible for fear of eliciting new, unsolvable complaints. I avoid eye contact. I focus on the computer, tuning out her words, as I copy from my previous note: “multiple somatic complaints, noncompliant with recommendations for psychiatric therapy.â€

I have tried to prioritize her complaints. I have tried setting modest, attainable goals. I have tried to reassure her of her basic good health. I have tried to placate her by ordering all the tests she requests. I have tried to set limits by refusing to order the tests she requests. I have tried to help her see the connection between stress and symptoms. Nothing helps.

And now I am angry.

“You are healthy,†I say to Ms. Uddin sternly. No reaction.

I turn to the daughter, with antagonism rising in my voice. “Tell your mother that she is basically healthy, and that most of these symptoms are probably related to depression, and that she needs to see the psychiatrist.†Azina’s face is blank as she translates.

After speaking, the daughter looks down at her sneakers, her light veil tumbling over her shoulders as she lowers her gaze. “Are you almost finished?†she asks.

It takes me a moment to realize that Azina is talking to me. This is the first time Azina has ever addressed me directly.

She looks up at me. “I have to take her home on the bus, and then I have to take another bus to school. I don’t want to miss the whole day.â€

“Can’t your mother come to clinic by herself?†I ask, a bit less testily. “We do have interpreters available.â€

“My mother is afraid to go out by herself,†Azina says, in a voice that wants to be belligerent but is too weary. “My brother is in college and my father works, so I have to take her to the doctor.†She stares back down at her sneakers, which have stopped banging and are now wriggling from side to side.

I turn from the computer for a moment, and really look at Azina. Her eyes are smooth sandalwood, magnified into iridescent discs by the thick lenses of her glasses. “What is it like at home?†I ask, quietly.

This is the first time I’ve ever addressed Azina as anything other than her mother’s mouthpiece.

“She doesn’t do anything,†Azina mumbles. “She just sits there.†Azina’s face has a prepubescent chubbiness that is somehow incongruous with the seriousness of her headscarf and glasses.

I turn in my chair to face her directly. Tears begin to slide down her cheeks, and her voice rises in a warble. “She doesn’t say anything to us. She doesn’t cook dinner anymore. She doesn’t go anywhere.â€

My mind begins to paint a picture of the Uddin home, and I see a little girl cut off from her mother, reeling in the wretched vacuum that depression creates—a child conscripted to be the fulcrum of cultures, illnesses, and torments, all while trying to complete fifth grade. I am mortified, now, that I was so consumed with my own feelings of being overwhelmed, when before me sits a child literally drowning—a child grasping the rickety timbers that can barely support her mother and that threaten to sink them both.

It is the innocence of this pain, its simplicity, that both shocks me back to reality and humbles me. I realize that never, in all my visits with Ms. Uddin, have I paid any attention to Azina; she was always a mere appendage to her mother’s appointments, trailing along, obediently translating and directing, as so many first-generation children do.

In medicine we always seek “objective data†to confirm a diagnosis, something that is often tricky with “difficult†patients. But Azina is the objective data, the stark evidence of the magnitude of my patient’s pain. Though I’d like to write Ms. Uddin off as just another complainer, as one who can’t hiccup without demanding an MRI, she is truly suffering. Her daughter is truly suffering.

I am not suffering.

I am actually the complainer. I’m the one who can’t face this patient without immediately rolling my eyes and turning off my compassion. The reality is that I am profoundly discomfited by my inability to treat Ms. Uddin, and she is simply the thorn that continually reminds me how limited my skills can be.

Though physicians do inquire about patients’ “social history,†as part of the full medical interview, it is usually given only lip service. We tend to view our patients as just that: patients. They exist only in our office, on our wards, in our clinics. We forget that 99 percent of their lives are lived—or suffered—without us. We often react as though their illness is a personal battle between doctor and patient, when, in fact, we are bit players. The real battle is between the patient and his or her world: spouses, children, work, community, daily activities. It is within this grander tapestry that the threads of bodily dysfunction introduce rents in the fabric, even wholesale unraveling. It is often only when we are allowed to glimpse the greater weave of our patients’ existence that we can truly understand what illness is.

I take the hands of both Azina and her mother, for they are both my patients now. “Depression is a painful illness,†I say. “Broken souls hurt as much as broken bones, and the pain spreads to everyone around them.†I explain about antidepressant medications and the importance of psychotherapy, and we negotiate a contract for treatment. This time, I include a stipulation that Ms. Uddin come alone or with her husband, that Azina must stay in school.

Azina wipes her tears. Ms. Uddin gathers her papers and snaps the veil back over her face. She promises to take the medications and to see the psychiatrist.

Of course, we have been down this road many times before, and I won’t be surprised if she’s back next month with a new physical ailment, not taking her antidepressants, having missed the appointment with the psychiatrist. And I won’t be surprised if I, again, dread the visit.

But I think, or at least I hope, that I will no longer view Ms. Uddin as a personal torment. Azina will cure me of that.