Medical Humanities: The Rx for Uncertainty?

Medical Humanities: The Rx for Uncertainty?

Medical Humanities: The Rx for Uncertainty?

by Danielle Ofri

Academic Medicine

It was just one nonfiction manuscript out of hundreds that were being considered for the Bellevue Literary Review. The essay was ragged at the edges, and it almost didn’t make the first cut. The narrator was a college kid on spring break in Florida. She was dancing at a disco, trying to pick up a guy. The Bee Gees were playing, the disco lights were flashing, the hormones were percolating. So far, standard chick lit.

But then, during one particularly exuberant dance move, the narrator’s prosthetic leg disengaged and went spinning across the floor. Horrified, she dropped down to see where it went. She crawled along a floor sticky with beer, worming her way around sweating, gyrating bodies. Desperate to find her leg, she shimmied through the crowd on her elbows, trying to stay focused despite the flashing lights and thudding beat. All the while, her date blithely boogied on, entirely oblivious to her terranean quest.

As an editor, it’s a special thrill to happen upon a diamond in the rough. Working with an author to coax a story into its final form is literary epinephrine. As a physician, though, a story like this is educational gold. Breaking Point1 became my go-to essay when I want to encourage my students to think about how we inhabit our bodies and to contemplate the blindness of those unaffected by illness or disability.

Somewhat akin to that famous description of pornography, we know good doctors when we see them, and we know lousy doctors when we see them. We all know doctors with brilliant medical knowledge but we’d never send our family members to them.

Typically, it is medical knowledge that students fear the most–memorizing all those diseases, passing the tests, not looking stupid on rounds. There is no doubt that mastering the facts of medicine is intolerably humbling and Sisyphean in its relentlessness. But that, in fact, is the easy part of medicine. Or at least that’s what many of us have realized once we’ve gotten past the avalanche that is medical training.

The hard part is how to translate that knowledge into wisdom. We don’t just want doctors to be smart; we also want them to be wise. We want doctors not just to be good but also to be great–the kind of doctor your grandmother writes home about. Translating knowledge into wisdom is one of the greatest challenges of medical education and it’s not something easily achievable with a PowerPoint presentation or a 1-to-7 Likert scale.

A key element in developing wisdom from knowledge is learning to tolerate ambiguity and uncertainty. This is a frustrating experience for most people but especially for doctors. The girder of medical culture is scientific certainty, and we rightly deride anything that isn’t evidence-based or peer-reviewed. But actual patient care–real people with real diseases–is steeped in uncertainty.

Living with uncertainty can feel like being on a slow-moving carousel–the vague unsettling sensation of not quite knowing where you are, your brain slightly muddled by cheery yet sinister carnival music, your stomach hovering just shy of nausea but still several degrees beyond comfort, your eyes disoriented from the absurd images that are moving too quickly for focus though not fast enough to qualify as a blur.

And then, in that state, doctors are asked to make serious and profound decisions, ones that may gravely impact the lives of fellow human beings. They are expected to render these decisions in a concise, definitive manner, with all the cool-headed flair of a person in charge. None of that namby-pamby waffling.

Indeed, a large part of our medical maturation is facing the uncertainty and then accepting it into our fold, getting acclimatized to the carousel and gathering our bearings in a disorienting world. This is far harder than memorizing all those rare diseases.

The humanities can offer doctors a paradigm for living with ambiguity and even for relishing it. Great works of literature, art, theater, and music specialize in ambiguity, confusion, and frailty. Unlike medicine, the humanities do not shy away from uncertainty. They revel in the depth and breadth that ambiguity affords.

When I read Breaking Point with my students, we are thrown, quite viscerally, into the beating heart of human vulnerability. Issues of disability, body image, and health no longer seem quite as clear-cut. Disabled versus abled doesn’t seem so binary any more, nor does illness. Most medical students–and most doctors, for that matter–have never grappled with these uncomfortable shades of gray. But our patients do, every single day.

The more familiar that doctors, and patients frankly, are with these states of discomfort, the more we realize that such states are normal. The more we allow ourselves to recognize these states of ambiguity within ourselves, the wiser and more nuanced we can be in our approach to patients.

In clinical practice and medical education, we spend our days plumbing the depths of the human body and its discontents. However, we rarely have the time or the emotional space to grapple with the ramifications of what we do. Slowing down is something doctors do not do well. We demand rapid results, from our diagnostic tests, from our patients, and most mercilessly, from ourselves. We rarely permit ourselves to wait in solitude, to allow the poetic subtleties and convoluted irrationalities of patient care to sink deep within us. It is both awkward and daunting to stop and wait. And so we walk and talk at a feverish clip to keep the reflective silence at bay.

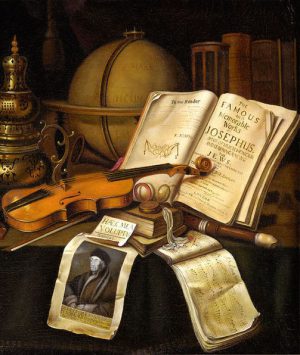

When I think about the role of the humanities in medical education, I return again and again to this reflective silence. Reading a poem, gazing at a painting, listening to a concerto–these all demand reflective silence. They force us to step back from the in-the-moment experience into the buffer zones of contemplation. Medicine is too often practiced only in the moment. This lack of contemplation coarsens our decision-making process, and it is our patients who suffer.

The reflective silence that the ambiguity of the humanities forces on us is salutary for our patients, but it is also beneficial for us. Exhaustion, numbness, and burnout, sadly, seem to be sine qua non’s of medicine. Everyone, at some time or another, has felt drained to the point of incoherence or has felt like an automaton mindlessly clicking the electronic medical record. Nearly everyone has, at some point, sunk into that abyss in which patients are viewed as the source of pain and the only goal is to get rid of them as expediently as possible. One commonality in these situations is a lack of reflective silence; we are generally left to stew in our wretchedness and ignominy.

The humanities allow us to develop the underused mental muscles of reflection and contemplation. They foster perspective and questioning. They emphasize context and provenance. They confront and relish ambiguity. Imagine having such tools at hand in the depths of one’s misery. They certainly don’t erase the realities that cause such states, but they offer balms for the pain, and occasionally the needed boost up to that first rung of the ladder out.

In some ways, the medical humanities function as a photographic negative for clinical practice, bringing light to places that are normally dark. In doing so, they allow doctors to explore the deeper context of what it means to be “in medicine.†They leaven the thought process to promote more nuanced thinking, something that stands to benefit both patient and doctor alike.

All of these pedagogical imperatives are indeed crucial. They fit approvingly into mission statements and grant applications. But beyond all these laudatory goals, there is the simple truth that the humanities bring joy. The academic medical path is known for many things, but joy isn’t typically one of them. If literature, art, music, and theater bring a measure of joy to our students who are waterlogged by pyruvate kinase, renal tubular acidoses, and terminal illness, that alone is a cause for celebration. Beauty and pleasure are rarely articulated as part of medical training. But there is a beauty in the complexity of the human body, and there is intense pleasure to be mined from the human connections that we are so fortunate to be privy to.

And so when I give advice to medical students and interns, I stay away from recommending cardiology over nephrology, or hospital practice over private practice, or New York over Boston. These young doctors are all smart and they will all land on their feet. Rather, I try to advise them on ways to stay engaged in the world. I ask them what their passion is, or what it was; what their hobbies are, or what they used to be. Most have wistful recollections of things they used to do, things they used to love, and they nearly always involve some aspect of the humanities. I press them to think of ways to stitch a little bit of these back into their lives, just enough to remain engaged, just enough to help keep their soul intact.

If you spend five fewer minutes reading the New England Journal of Medicine, I promise them, you’ll still be a good doctor. You won’t kill any patients for missing those five minutes. But if you squeeze in five minutes of Brahms or Noguchi or Louise Gluck or August Wilson, if you find five minutes to pick up your French horn or your watercolors or your tap shoes, then you will be more fully engaged in the world. You’ll stretch those off-the-beaten-track neurons that then will be there for you the next time you confront an inscrutable diagnosis, an uncertain treatment plan, or a seemingly unreachable patient. You might just find in the palm of your hand that nugget of creativity that squeezes you past a block that stymies others. You might make that transition from being a smart doctor to a wise doctor, from a good doctor to a great doctor. And not only will you be a great doctor, but you’ll also be a great person. And then your grandmother will really have something to write home about.

References

- Cronin ME. Breaking Point. Bellevue Literary Review. 2008;2:58-61.