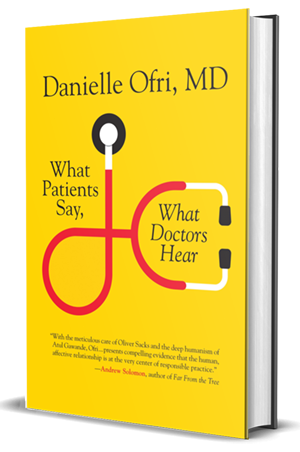

McGill News review of “What Patients Say,What Doctors Hear”

by Wendy Helfenbaum

McGill News

Twenty minutes. That’s the average length of time that a doctor spends with a patient. Squeezing in a medical history, a physical exam and diagnosis, plus explanations for medications, can be a challenge. Many physicians struggle to treat their patients while adhering to their very tight schedules. What happens when there’s a huge disconnect in this very intimate relationship?

Danielle Ofri deals with these issues every day. For more than 20 years, she has treated patients at Bellevue Hospital, the largest public hospital in the U.S. She’s also an associate professor at the New York School of Medicine, and a prolific writer whose work exploring the doctor-patient relationship has appeared in the New York Times, the Washington Post, the New England Journal of Medicine, and on National Public Radio.

In her recently published fifth book, What Patients Say; What Doctors Hear, Ofri argues that while modern medicine touts high-tech tools and techniques, the single most powerful diagnostic tool continues to be the doctor-patient conversation.

As a practicing physician, though, Ofri was well aware that patients and their doctors often aren’t listening to each other. Nervous about their health, patients may ramble, while time-strapped physicians might hurry through the appointment, increasing the risk of misdiagnosis or medical error.

“The conversation is the most important thing that takes place between a doctor and patient and should be treated that way. I would love to see it be reimbursed the way an MRI is,†says Ofri. “When I talk with a patient for 20 minutes about their medication adherence, that probably has a bigger outcome on their health than the $500 CAT scan I ordered. My visit will be reimbursed $40; that’s just the way it’s valued. My ultimate hope is that on a policy level we change how we think.â€

Ofri suggests patients prioritize their most important questions in advance, and doctors resist the urge to interrupt or multi-task during appointments.

“If I take three minutes and focus 100 per cent, a lot of concrete information can come from that. Also, the patient feels very respected, and I think that’s the investment in the relationship.â€

Ofri cites an NYU study in her book revealing that when doctors dominate conversations, the risk of patients not taking their medications is three-fold higher. Patients who don’t feel ‘heard’ are also more likely to sue for malpractice, she notes.

To that end, Ofri is pleased that many medical schools are finally realizing that training doctors to listen to their patients must be an ongoing process.

“As doctors, we jump to speak so quickly; If we stopped and listened I think we’d realize that often our first assumptions are not correct,†she says. In her book, she mentions McGill associate professor of medicine Donald Boudreau’s pioneering course on attentive listening as a step in the right direction.

A native New Yorker, Ofri has warm memories of her time at McGill.

“Coming to McGill made me a stronger believer in serendipity,†she says. “First, I took an apartment on Durocher, put up a sign for roommates and chose the first two people that walked in; they’re still my closest friends. Then, I met a student who said, ‘If you don’t take a course with Yiddish literature professor Ruth Wisse, you’ve wasted your education at McGill.’ I was in the physiology program with no literature requirements at all, and Dr. Wisse opened up a whole other world.â€

Wisse is now a professor at Harvard, but her influence on Ofri remains intact. After completing her medical training, Ofri signed up with a physician’s staffing agency where she worked in clinics across the U.S. and travelled between gigs. During those 18 months of seeing patients and seeing the world, Ofri began chronicling her experiences in medicine.

“I trained during the height of the HIV epidemic – a very intense time – and I knew these were unique stories,†she recalls. “When I finally was away physically and temperamentally from the hospital, I wrote.â€

She eventually co-founded the Bellevue Literary Review, a unique literary journal that focuses on issues of health and illness (she continues to serve as its editor-in-chief) and has now published five books that examined various aspects of medicine.

“It’s so nice to not worry about someone’s aortic stenosis, and worry about their stanza formation instead,†she says of her literary pursuits, but she insists that her first calling will always be medicine.

“I feel so blessed, particularly working with an underserved population. I’m often the only doctor they have, and if I help them get a social work referral or find out where they can get physical therapy or dentures covered, it makes an enormous difference. What’s better than that?â€