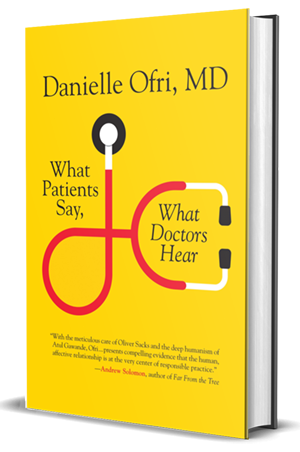

Lancet review of “What Patients Say; What Doctors Hear”

by Audrey Schafer

The Lancet

“For all the sophisticated diagnostic tools of modern medicine, the conversation between doctor and patient remains the primary diagnostic tool.” This idea lies at the heart of Danielle Ofri’s new book What Patients Say, What Doctors Hear, in which she acknowledges, dissects, experiments with, and analyses the complexities and miscues of the patient-doctor exchange.

In an extended thread woven throughout the text, Ofri follows a patient and her doctor through the patient’s harrowing illness. The reader learns how the patient and her physician interpreted, in vastly different ways, what was said at numerous junctions in the patient’s journey through diagnosis and treatment. By choosing an example of both a well intentioned, caring physician, and an informed, intelligent patient, Ofri highlights that issues of miscommunication occur even under conditions of high-quality, humanistic health care.

Throughout the book Ofri also relates anecdotes about her doctoring mishaps and her efforts to improve her listening and communication skills. Citing the classic study that showed the average time to interruption by a physician of a patient’s story is 12 seconds, Ofri succeeds in changing her practice to give the patient unlimited time at the front end of the visit to describe what is going on and why the patient came to the doctor. She is surprised at the results: on average her patients take less than 2 minutes, replicating the Swiss study she had read.

I found the chapter Rushing to Judgment especially noteworthy. Ofri examines the realm of prejudice, implicit bias, and the health effects of race, gender, addiction history, and other differences between patient and doctor in terms of diagnosis and treatment. She begins with bias against obesity, which undermines respect and trust whether it is the patient or the physician who is obese. Ofri finds that the more she is able to talk with her morbidly obese patient, the less burdensome the physicality of the patient becomes—that is, the human story emerges. Prejudice affects health: “African Americans and other racial and ethnic minorities consistently receive less-aggressive cancer treatment, fewer cardiac catheterizations, fewer screening tests, less mental health treatment. The list is depressingly long,” Ofri notes. Although she doesn’t specifically address micro-aggressions, intersectionality, and other aspects of bias and identity, Ofri does offer the right directive: make “a determined effort to see the other person as a unique individual and then [take] the next step of envisioning that person’s perspective.”

As a doctor, I have made some grievous communication errors; one event decades ago still haunts me. I was a medical intern on the intensive care rotation. We had had five codes already across the hospital that Saturday morning. One was perplexing: a psychiatric patient with kidney failure went into cardiopulmonary arrest after replacement of his temporary dialysis access line by the renal team. The resuscitation was “successful” and we transported our new patient to the intensive care unit. Other than communication, he met criteria for extubation. The nurse told me the patient’s mother was waiting. I met the mother in the hall, as we had no waiting room. She, like her son, was African American. I am white. She was in her 60s, I was in my 20s. She was a parent, I was not. She said she wanted to see her son. I said, it would be better to wait 15 minutes, then she could see him without the tube. She paused, then agreed to wait. I hurried back to the busy intensive care unit. Shortly thereafter, while the patient breathed spontaneously through his endotracheal tube, he coded again. This time, he died. If I had listened, stopped to imagine what a mother might feel, or reflected on the history of racism and distrust in health care, perhaps I would have heard her differently. But I didn’t do any of those things. She was her son’s only voice. I replay the words we exchanged. I remember her pause. I don’t think the patient’s death was related to communication, but his mother would have seen her son, one more time, alive, if I had truly listened.

Ofri’s compelling book, useful to doctors and patients alike, provides not only a humble, entertaining, and insightful entré into her practice, but also a guide to many facets of communication. Like her fellow physician-author at New York University, Perri Klass, Ofri can be laugh-out-loud funny. She brings us to her cello lessons to witness, with self-deprecating humor, how listening is a process and a practice, and how middle C is not as easy to find as on her “long-suffering piano.” She notes, “after a century of assuming that two ears affixed to a skull was sufficient preparation” for listening, medical schools are finally concluding that listening skills must be taught and addressed. Communication, including fully present, attentive listening, is vital to medical care, for the health and wellbeing of all involved.