Boston Globe Book Review: “Singular Intimacies”

By Caroline Leavitt

Boston Globe Book Review

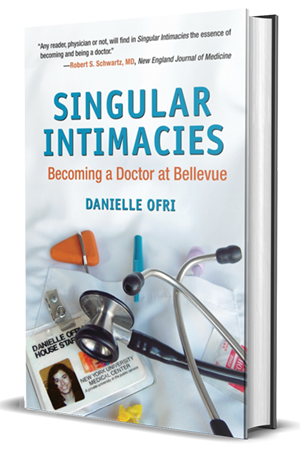

When people pass around that old chestnut that doctors can’t be emotional if they want to do their jobs properly, I always cheerfully disagree. The thing I remember most about my obstetrician (besides his expertise) was that he cried out in wonder, ”Oh, he’s beautiful!” when he delivered my son. During one terrible year when I was critically ill, one of my surgeons wrote me a heartfelt letter that strengthened me with each reading. I knew that my doctors were as sensitive to me as they were to what was going on with my body, that rather than stoic practitioners, they were also deeply, emotionally, human. Maybe that’s why Danielle Ofri’s ”Singular Intimacies: Becoming a Doctor at Bellevue” about the emotional life of doctors and their patients, captivated me so much. Ofri is fascinating not just because she’s an attending physician at Bellevue, ”the oldest and craziest hospital in the nation,” but because she’s also the cofounder and editor in chief of the revolutionary Bellevue Literary Review. Ofri began the journal as a way to get doctors to think more about the role emotions play in healing. Every patient’s history, she says, is a narrative that unfolds full of surprises, and doctors need to understand how and why each story is part of good medical care. Discovering that someone lives on the street means they can’t change their dressings easily, so outpatient care has to do it. Knowing that a patient’s afraid of being labeled a drug addict at work may mean he won’t take his meds during working hours, so a doctor had better adjust the dosage.

Ofri bares her soul, from anxious-to-succeed intern thrust into the ”slippery chaos” of an urban hospital to seasoned doctor determined never to treat a patient like a statistic. Wonderfully human, she lets us see her clay feet. She hates some patients. She screws up. In the gripping chapter ”M & M” (morbidity and mortality), she chronicles the medical decisions that ended a patient’s life. ”I cried for my belief that intellect conquers all,” she says.

It’s this marriage of intellect and emotion that makes ”Singular Intimacies” read like a deftly crafted and luminously written novel. Haunted by the death of a friend, Ofri uses her grief to ensure she always sees the person inside the patient. In one of the book’s most gripping scenes, she’s stuck by a needle in the OR and, horrified, visits the patient in a clumsy attempt to find out if she might have contracted AIDS from her. Ofri’s fear is so palpable that she ends up being comforted by the patient — an encounter that’s healing for both.

While Ofri interacts with all varieties of patients on all sorts of levels, the denizens in Michael Ruhlman’s astonishing ‘‘Walk on Water: Inside an Elite Pediatric Surgical Unit” (Viking, $24.95) are all babies, who ”don’t know anything else but living.” And what’s most terrifying is that unless a doctor can repair their walnut-size hearts — they die.

Because Ruhlman relates the stories here, instead of the surgeons themselves, it’s a little less intimate a read — but no less thrilling. Ruhlman’s gotten deep inside the hearts and minds of these surgeons to re-create the ”brutal and beautiful” world of pediatric surgery, focusing on Roger Mee, the surgeon who can ”walk on water” at the world-famous Cleveland Clinic Center for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. There’s a lot at stake here, and the language used to deal with the procedures — the narrative, as Ofri would call it — is horrifying. Pediatric surgery is so dangerous that it’s described as having a license to kill. Mee, himself, worrying over a tiny patient, says, ”I just don’t know if I’m going to assassinate this kid.” But in a world like this, harsh language is necessary. ”You can’t hide when you’re a peds heart surgeon,” says one doctor. ”You know who you are and where you stand. Because there’s so much at risk, there’s no room for dishonesty.” This is a world where the unthinkable always happens: A mother must shake her baby — something associated with abuse — to keep it alive. A newborn, taken off life support to die, instead breathes on his own for the first time since he was born.

The doctors here called Ruhlman their conscience, and he doesn’t shy from exploring the ethics. ”The biggest risk factor is being admitted to the wrong institution,” one doctor insists. Patients don’t realize they should ask about mortality rates at different hospitals, and hospitals, responsive to insurance companies, often refer patients not to the best centers, but to the nearest, with potentially devastating consequences. This, plus the life-or-death pressure of pediatric surgery, can make or break caring doctors. ”I never want to operate again,” says one weary doctor after a failed procedure.

As much as Ofri stresses the need for doctors to feel, Ruhlman makes you understand why a pediatric surgeon might resist. But feel these doctors do. When babies die, says one surgeon, ”we cry and cry. The day that I don’t, I’ll go back to India.”

These two incredible books make an intense story out of medicine. Exploring this emotional terrain doesn’t just humanize doctors. I think it humanizes patients, too, making us both more responsible for — and responsive to — the healing that goes on for doctor and patient both.

This story ran on page E9 of the Boston Globe on 4/27/2003.