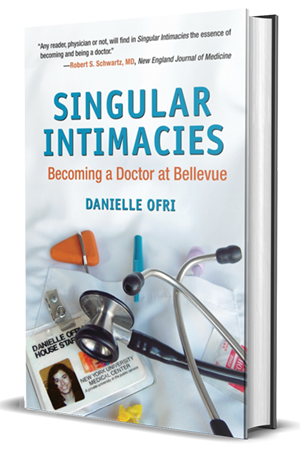

NEJM review of “Singular Intimacies”

by Robert Schwartz

New England Journal of Medicine

Bellevue Hospital, probably the oldest hospital in America, began to serve George II’s New York subjects in 1736 as a Public Workhouse and House of Correction with six beds for the sick. Included in the cost of construction were 50 gallons of rum. Forced by an epidemic of yellow fever to escape the filth of central Manhattan in 1794, the almshouse–prison–hospital complex found a haven at Belle Vue, an estate overlooking the East River. Bellevue became a teaching hospital, first by shedding its poorhouse and penitentiary and then, in 1847, by opening its doors to medical students. The horse-drawn wagons of the world’s first hospital-based ambulance service began to clatter out of Bellevue in 1869, and four years later the hospital opened America’s first nursing school. Over the ensuing years, Bellevue evolved into a behemoth built of bricks the color of dried blood, one side facing the East River, the other looming over First Avenue and 27th Street. In the 1950s, New York University medical students, of which I was one, thought it was the greatest hospital in the world’s greatest city. The Old Bellevue is now a worn-out hulk occupied mainly by administrators. Its clinical services were transferred to the New Bellevue in 1973, and a part of the former poorhouse is undergoing conversion into a center for biomedical research.

Now, 30 years after the Old Bellevue closed its doors to the sick, Danielle Ofri recounts in Singular Intimacies how it was to be a medical student and resident at the New Bellevue and how it is to serve the grande dame of New York medicine as an attending physician. Ofri is a gifted writer. Her vignettes ring with truth, and for any physician or patient who knows the dramas of a big-city hospital they will evoke tears, laughter, and memories. Indeed, any reader, physician or not, will find in Singular Intimacies the essence of becoming and being a doctor.

Ofri’s prologue tells the story of a 62-year-old French woman with lung cancer who, gasping for breath, gives the intensive care unit (ICU) team her final orders through an oxygen mask. “Air France,†she says. “No other airline. My body must fly to Paris via Air France. . . . No ceremony before the interment . . . just a burial at Rue de la Colonnade.†Ofri writes, “We file out of the room . . . our hands dangling awkward and useless, our tears threatening to give way.†Ofri’s epilogue reveals that after a week in the ICU, her French patient’s pulmonary infiltrates and hypoxia gave way to antibiotics. “There was no sweeter music than that silvery Parisian accent floating into my ears. . . . The arc of her words shimmered in the air and her history settled softly into mine.†Little wonder that Danielle Ofri is editor-in-chief of the Bellevue Literary Revue.

Then there is “The Professor of Denial,†a psychiatrist who is clearly in the terminal stages of an intra-abdominal cancer but does not have a tissue diagnosis. The psychiatrist insists to the end that he has viral hepatitis. Despite obvious signs of his patient’s impending death, Dr. Gursky, the attending physician, demands one invasive diagnostic procedure after another, including a laparotomy, to get the answer. All to no avail. Ofri’s anguish at having to carry out Gursky’s orders is the only point of clarity in this story. One wonders who was in denial — the patient or Dr. Gursky.

Ofri writes about Mrs. Whitney from South Carolina, whose brain lost its cortical function after she collapsed from cardiac arrest while visiting her daughter in New York. All the frustrations of caring for a patient in a vegetative state in the cardiac care unit of Bellevue Hospital and dealing with her family are examined. “It’s just a coincidence that her eyes sometimes move toward you when you speak. But her cortex can’t process anything they’re seeing. I . . . I’m sorry.†The arresting aspect of the story is Ofri’s respect for the unseeing, unfeeling Mrs. Whitney and her hope that the staff that will continue Mrs. Whitney’s care will “find the person within the patient.â€

In these and 13 other stories, Ofri distills the terrors, frustrations, and joys of her life as a student and physician at Bellevue. Above all, Ofri has the precious gift of humility. It is this quality that graces her prose, transforming it from mere storytelling into memorable parables.