Coming Home to Bellevue

by Danielle Ofri

by Danielle Ofri

New York Times

There’s no place like home. That’s not a phrase people typically utter about their hospitals, but those were the words on everyone’s lips when we returned to Bellevue last week, after nearly a month of dislocation since the hurricane-induced evacuation at the end of October.

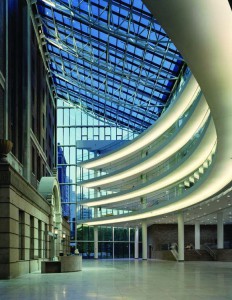

It was a celebratory atmosphere last Monday, when Bellevue Hospital officially reopened its doors. Colorful balloons and “Welcome Home” T-shirts filled the atrium, as staff and patients streamed in. The relief was palpable as we marked the end of this period, Bellevue’s first sustained closure since 1736.

All was not magically renewed, of course. The damage to the operational innards of the hospital building, caused when Hurricane Sandy flooded the basement with some 10 million gallons of seawater, was such that the inpatient service will not open for months. The medicine, pediatrics and gynecology clinics reopened last week. A handful of the subspecialty clinics opened Monday, but the other clinics and the operating rooms remain scattered in hospitals across the five boroughs, an arrangement that has come to be known affectionately as the Bellevue diaspora.

More than 500 of Bellevue’s doctors and physician assistants, and hundreds of other staff members and medical students, were sent to various local hospitals. Though the evacuation during the hurricane was a dramatic event, the number of inpatients affected (500 evacuated, 275 discharged) was quite small compared with the tens of thousands of outpatients who rely on Bellevue for their medical care.

The doctors of my clinic – internal medicine – had set up camp at Metropolitan Hospital, another New York City public hospital, in a tiny concrete-block annex in a parking lot. The experience was humbling and disorienting for us – perhaps a taste of what life is like for our patients as they navigate the health care system in normal times.

I shared a cubicle with two other doctors and a stretcher overflowing with a dozen winter coats and bags. We three squeezed around an adjustable tray table, the kind bed-bound patients use for meals, where a single laptop for accessing medical records was set up. Ten residents and physician assistants shimmied in and out of the narrow space to discuss cases.

Patients thronged the makeshift clinic, desperate to renew medications, follow-up on X-rays, blood tests and consultations and continue evaluations initiated before the storm. At times the front door could not be opened because of the crush of bodies.

No one was complaining, of course: We were grateful for the space, as were our patients. Our hosts were welcoming beyond expectation, despite the strain. But logistical hurdles were legion.

For instance, electronic medical records. To generate prescriptions or order blood tests, we had to use Metropolitan’s system. This required the cumbersome clerical bottleneck of first registering these thousands of Bellevue patients into it. But we also needed to retrieve the medical records from the Bellevue system to figure out which medications patients had been taking for what conditions, the results of important blood tests, and other information vital to treatment.

So for each patient, we toggled back and forth on our single computer between two medical record systems and two different medical record numbers. The systems were similar enough that – in a moment’s glance – it wasn’t always obvious which system you were in, but different enough for reflexive habits to jam up the works. And then there was always the nerve-racking worry that this jiggling back and forth between systems could introduce errors along the way.

On top of this was the confusion of trying to figure out where our various medical services had ended up. Hand-scrawled messages were taped to our cubicle wall: Psychiatry was at Metropolitan; the Cancer Center at Woodhull Hospital in Brooklyn. Dermatology was seeing patients at Gouverneur Healthcare Services in Manhattan, but only on Wednesdays and Thursdays. Rheumatology was available by phone. Dialysis was at Jacobi in the Bronx. The surgeons were divided up between Harlem Hospital, Metropolitan, Gouverneur and Woodhull. Internal medicine was seeing outpatients at Metropolitan and Gouverneur, but also at Elmhurst, in Queens, and staffing two evacuation shelters 24/7. Internal medicine teams were also covering inpatients at nine different hospitals. But many of these were moving targets; each day a few locations were crossed out and new ones added.

Morale, though, was surprisingly buoyant. The Metropolitan staff members were superb and went out of their way to help us. A colleague who was sent to Jacobi sent me a photo of the chief of medicine there handing out welcome bags of snacks to the Bellevue medical residents. The chief made sure the Bellevue team had its own conference room, and installed a water cooler and microwave to make life easier.

The first time I ran into one of my patients at Metropolitan, we practically knocked each other over in a bear hug. We were so relieved to have found each other; it was almost like a family reunion. We commiserated about our respective experiences post-hurricane, living without electricity, water, heat and phone. She was nearly out of her blood pressure medications and worried that she wouldn’t be able to get more.

It has been an exhausting and challenging time for all of the Bellevue staff, but there were also unexpected positives. “At my age,” confided one of my colleagues who had been posted to Queens Hospital, “any change is reinvigorating and maybe even rejuvenating.”

Most of us have spent years figuring out the kinks and shortcuts in the complicated warren of Bellevue. Now we attempted to replicate those procedures in unfamiliar hospital buildings, stumbling through new medical records systems and trying to find the point persons for IT, phlebotomy, pharmacy, and how to get X-rays, chemotherapy, and coffee.

Despite the generosity of our hosts, most of us felt unsettled throughout this period. The sense of displacement was pervasive and distinctly uncomfortable. But if every change is a learning experience, this was an important one for the medical staff. Feeling lost, confused, unsure what to do or where to go is not too dissimilar to the experience of being ill. Navigating illness – like navigating a post-hurricane displacement – is disorienting, frightening and intensely disrupting.

For all the disquieting feelings the doctors experienced, the patients suffered the brunt of the dislocation. By the time we saw them, many had the exhausted look of refugees. It had taken days after the hurricane, sometimes more than a week, to figure out where to find us. Once arriving, they waited hours, navigating a confusing, foreign system. They had missed days of medication during the storm and its aftermath, and were worried about their scheduled colonoscopies, CT scans, cataract surgeries, physical therapy sessions. Would any of these take place? Frustratingly, we did not always have answers for them.

Bellevue continues the arduous cleanup and repair. Complete reconstitution will probably notoccur until the new year, and many doctors will remain deployed at their host hospitals until then.

Bellevue continues the arduous cleanup and repair. Complete reconstitution will probably notoccur until the new year, and many doctors will remain deployed at their host hospitals until then.

Those of us who were able to return to Bellevue in the first wave were deliriously grateful to treat our first patients “at home.” But we would do well to hang on to some of the unsettling feeling of displacement. It may prove to be an unexpected gift of empathy for our patients’ experiences.