Merced

©Beacon Press, 2009

“Merced†won the Editor’s Prize for Nonfiction in The Missouri Review, and then appeared in Best American Essays, 2002. It was then incorporated in Danielle’s first book Singular Intimacies: Becoming a Doctor at Bellevue.

“This is a case of a 23 year-old Hispanic female, without significant past medical history, who presented to Bellevue Hospital complaining of a headache.†The speaker droned on with the details of the case that I knew so well. I leaned back in my chair, anticipating and savoring the accolades that were going to come. After all, in a roundabout way, I’d made the diagnosis. I was the one who had the idea to send the Lyme test in the first place.

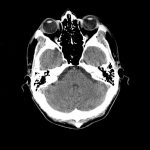

Mercedes had been to two other ERs before showing up at Bellevue three weeks ago. I was only doing sick call that day because, Roger, one of the other residents, had twisted his knee playing volleyball. Mercedes was a classic aseptic meningitis, the kind that you’d send home with aspirin and some chicken soup, but the ER had decided to admit her to the hospital. Her CT scan was normal, and the spinal tap just showed a few lymphocytes, but the ER always overreacts. They gave her IV antibiotics even though there was no hint of the life-threatening bacterial meningitis.Â

One of the ER docs had scrawled something about ‘bizarre behavior’ on the chart and had given her a stat dose of acyclovir. Another ridiculous ER maneuver; this patient had no signs of herpes encephalitis.

I’ll admit that I was a little cocky that day. But I was just two months short of finishing residency and I knew a lot more medicine than those ER guys. I chewed them out for admitting her, and made a big show of canceling the acyclovir order.

When I met Mercedes on that first day, she was sleeping on a stretcher in a corner of the ER. I had to wake her up to take the history, but after a few shakes she was completely lucid. With her plump cheeks and wide brown eyes, she didn’t even look seventeen, much less twenty-three. The sleeves of her pink sweatshirt were pushed up past her elbows. A gold cross with delicate filigree was partly obscured by the folds of the sweatshirt.

“Doctor, you have to believe me,†she said, pulling herself up on the stretcher. “I’ve never been sick aday in my life. It’s only this past month that I’ve been getting these headaches. They come almost every day and aspirin doesn’t do anything. I came to the ER yesterday but they said, ‘You got nothin’ lady,’ and just gave me a couple of Tylenols.†Dark curls spilled over her pink shirt. They were mussed with a gentle just-woken-up look. While she spoke, one hand wove itself absentmindedly in and out of the locks.

“So, what made you come back today?†I asked.

“This headache, it didn’t go away. And then my arm. It got all pins and needles for a few minutes. Just a couple of minutes, but now it’s fine.†Mercedes smiled slightly, and two tiny dimples flickered in her cheeks. “I guess they got tired of me complaining, so they decided to let me stay.â€

I did a thorough physical exam, spending extra time on the neurologic part. I checked every reflex I could think of: biceps, triceps, brachoradialis, patellar, plantar. I examined all twelve cranial nerves. Everything seemed normal. I tried to do all the obscure neurological tests I could remember from Bate’s Textbook of Physical Diagnosis, but nothing seemed amiss. She was certainly not behaving bizarrely.

From talking to her, I learned that Mercedes was a single mother with two children aged three and four. She lived with her own mother, but still maintained a close relationship with the father of her children. She worked as a preschool teacher in upper Manhattan. She was born in Puerto Rico but since moving to the U.S. at age two, had never left the country.

I questioned her extensively about possible exposure to viruses or atypical organisms: travel to the countryside, recent illnesses, recent vaccinations, outbreaks of sickness at her preschool, HIV risk factors, contact with pets, poorly cooked fish or meat…. all of which she denied.

Based on her history and physical exam, I concluded that she had garden-variety aseptic meningitis. The ER staff, with their usual sledgehammer approach to medical care, had overdone it with intravenous antibiotics and acyclovir. Mercedes didn’t even need to stay in the hospital, but she’d already been officially admitted. The administrative folks would have a conniption if I sent a patient home just two hours after checking in.

Just to show the ER docs how real academic medicine was done, I wrote up an extensive admission note for Mercedes, detailing all the rare causes of aseptic meningitis listed in Harrison’s. Paragraph after paragraph elucidated my clinical logic, a textbook example of orderly scientific thinking. And I printed neatly, so it would be easy for anyone perusing the chart to read.

There was an extra tube of Mercedes’ cerebrospinal fluid sitting in my pocket, so I decided to send it for a couple of rare tests, including a Lyme titre. What the heck, I thought. This is a teaching institution. We’re supposed to waste some money on exotic tests in order to learn. Beside, it would really impress the attending on rounds tomorrow, when I would blithely nod my head at each diagnosis he’d ask about.

There was an extra tube of Mercedes’ cerebrospinal fluid sitting in my pocket, so I decided to send it for a couple of rare tests, including a Lyme titre. What the heck, I thought. This is a teaching institution. We’re supposed to waste some money on exotic tests in order to learn. Beside, it would really impress the attending on rounds tomorrow, when I would blithely nod my head at each diagnosis he’d ask about.

Lyme? “Done.â€

Rickettsia? “Got it.â€

Sarcoid? “Covered.â€

Cosackievirus? “Sent it.â€

Toxoplasmosis? “Already there.â€

Lupus? “Done.â€

The ER docs might just toss a heap of medications at anyone who walked in the door, but here in the Department of Medicine, we utilized our diagnostic acumen.

The next morning during rounds, just as I was dazzling the crowd with my erudite analysis of Mercedes’ case, the nurses called me urgently to Mercedes’ room. Mercedes was on the floor with her clothes off, hair askew, babbling incoherently. Her IV had been pulled out and her body was splattered with blood. Completely disoriented, she fought us vociferously as we tried to help her back to bed.

Thirty minutes later she was entirely back to normal – soft-spoken, polite, appropriately responsive to our questions, neatly groomed. She had no recollection of what had occurred and I was absolutely dumbfounded. What the hell had just happened?

Immediately I repeated a CT scan and spinal tap, but the results were no different than they’d beenthe day before. The neurologist felt Mercedes’ behavior might have represented a seizure of the temporal lobe. The herpes virus has a predilection for the temporal lobe so this episode might have been a sign of herpes encephalitis. Regretting my earlier haughtiness toward the ER staff, I quietly restarted the acyclovir.

Mercedes was transferred to the neurology unit for management of herpes encephalitis, and I was transferred off the ward when Roger’s knee got better. I was happy to get back to my cushy dermatology elective.

A week later, still smarting from missing the herpes encephalitis diagnosis, I tracked down the intern to see how Mercedes was doing. “Hey, did you hear the news?†he asked. “That herpes encephalitis patient really had Lyme disease. The test just came back positive yesterday.â€

Lyme disease? The Lyme test I that I had sent came back positive? I was exhilarated. This would be the most fascinating diagnosis on the medical wards. Who would have suspected that a New York City dweller would have a disease carried by deer ticks in the forest. But hey, I did a careful diagnostic evaluation of the patient, and my thoroughness paid off.

Soon everybody was talking about the case of Lyme meningitis in our inner-city hospital. The head of my residency program became interested in the case and suggested I plan a seminar on Lyme disease. I set about obtaining all the details of Mercedes’ case and searched the medical literature for current articles on Lyme disease.Â

Meanwhile, Mercedes was started on the appropriate medication for Lyme. She’d been discharged home and was finishing her three-week course of antibiotics with daily shots in the clinic.

Today the case was being presented at neurology grand rounds. I wasn’t a participant in this particular conference, but I didn’t care. I sat back in my chair and listened to speaker after speaker comment on the “incredible diagnosis†that had been made. My bulging ‘Mercedes/Lyme’ folder sat on my lap as I took mental notes, preparing for my own presentation in the Department of Medicine two weeks from now.

Today the case was being presented at neurology grand rounds. I wasn’t a participant in this particular conference, but I didn’t care. I sat back in my chair and listened to speaker after speaker comment on the “incredible diagnosis†that had been made. My bulging ‘Mercedes/Lyme’ folder sat on my lap as I took mental notes, preparing for my own presentation in the Department of Medicine two weeks from now.

Residency would be over at the end of next month. I had been here for ten years, from the beginning of medical school, through my PhD and then my residency. Ten years of medical training! But now it was truly paying off. Ten years of the scientific approach to medicine had prepared me for this case. Ten years of emphasis on careful analysis of data – whether of receptor binding assays in the lab, or signs and symptoms in a patient – had taught me how to establish a hypothesis and come to a logical conclusion. This was the academic way that ensured the highest quality medical care. Our attendings were always pointing out medical disasters that occurred ‘out in the community’ with doctors who were not academic physicians. Doctors who didn’t keep up with the latest medical journals. Doctors who, without diligent and thoughtful analysis, ordered any old test or prescribed any fancy packaged medicine marketed by the pharmaceutical companies.

Mercedes was lucky to have come to an academic medical center rather than to a community hospital, where her diagnosis would have been missed entirely. Just like Mr. Wiszhinsky on my first day at Bellevue as a medical student. His life was saved by his good fortune of coming to Bellevue

What a fantastic case for my residency training to culminate with. I could use this as an illustrative diagnostic case for my students of the future. Maybe I would submit this to the New England Journal of Medicine.

Someone had invited Mercedes to the conference, and she sat in the back listening quietly. I watched her from my vantage point in the corner. She looked wonderful on that Friday afternoon– no hint of the illness that caused that bizarre episode on her second hospital day. I shook her hand heartily and congratulated her on her recovery. Her hand was warm and plump, and her handshake reassuringly healthy.

Monday morning I joined our new team in the ICU. This was my last month of residency and I was going to spend it in the ICU. There was a crackle in the air of all the different machines breathing life into our critically ill patients. We rounded on all of our new patients as a tightly honed team, talking in easy jargon with no need to translate for anyone. At each bedside was a computer that was loaded with data for each patient. We raced each other to calculate arterial-alveolar gradients and oxygen extraction ratios. We reeled off ventilator management strategies, debating the relative values of positive end-expiratory pressure versus continuous positive airway pressure. I marveled at how easy it all was. As an intern, or even a second-year resident, the ICU was a terrifying place, especially the first day. But now I took it all in stride. Just another twelve sick patients on ventilators with arterial lines and Swans. Let ‘em crash, let ‘em code ….I knew I could handle it. That’s what ten years of Bellevue training does for you. Once you’ve been in the belly of the beast, nothing fazes you.

Monday morning I joined our new team in the ICU. This was my last month of residency and I was going to spend it in the ICU. There was a crackle in the air of all the different machines breathing life into our critically ill patients. We rounded on all of our new patients as a tightly honed team, talking in easy jargon with no need to translate for anyone. At each bedside was a computer that was loaded with data for each patient. We raced each other to calculate arterial-alveolar gradients and oxygen extraction ratios. We reeled off ventilator management strategies, debating the relative values of positive end-expiratory pressure versus continuous positive airway pressure. I marveled at how easy it all was. As an intern, or even a second-year resident, the ICU was a terrifying place, especially the first day. But now I took it all in stride. Just another twelve sick patients on ventilators with arterial lines and Swans. Let ‘em crash, let ‘em code ….I knew I could handle it. That’s what ten years of Bellevue training does for you. Once you’ve been in the belly of the beast, nothing fazes you.

That evening I was home alone, gathering my thoughts about my new set of patients. It was only Monday, but I knew it was going to be an exciting month. Residency was going to end in style. Our team was going to get this ICU into top shape.

But the old guy in Bed 5 who’d stroked out last month – left side not moving, already demented from Alzheimer’s. I wasn’t sure if his ventilator settings were optimized; his peak pressures had been fluctuating. I was sure I could do better. If I could get the latest blood gas results now, I could make the adjustments over the phone and then see his progress before rounds in the morning. Why wait until tomorrow if I could keep that patient one step ahead? I propped my feet up on my couch and tore open a bag of chili-and-lime tortilla chips. One hand dialed the phone while the other plunged into the bag. This was going to be a great month.

Instead of the clerk who usually answered the phone, George, one of the other residents happened to answer. We chatted for a while about how much fun the ICU was and what a great way it was to end residency. We discussed the ventilator management of Bed 5 and agreed to lower the flow rate but increase the tidal volume. I asked how his first night on call was going.

“What a night,†George said. “We’ve been incredibly busy. One cardiac arrest, one septic shock. But my third admission is the most interesting. It’s a good one. You ain’t never seen this before.â€

“Really,†I said, pulling out a handful of red, powdery chips. “What did you get?â€

“It’s a surprise. Something rare. You’ll see on tomorrow’s rounds.â€

“Give me a hint,†I said between chomps of chips. “I covered for you on your anniversary last March. You owe me one.â€

I pestered him some more, and then he finally relented. In a conspiratorially low voice, to tantalize my curiosity he said, “Read up on Lyme meningitis for rounds tomorrow.â€

The chips and chili turned to sawdust in my mouth. I blinked a few times, my brain slow to react. “That’s strange,†I said, the words like cardboard wading through the sawdust. “I just had a case of Lyme meningitis three weeks ago.†I could feel the muscles in my neck tightening. My throat began to constrict. Please God, don’t let it be the same person. Don’t let it be Mercedes.

“Yep, that’s the one,†George said.

Mercedes? In the ICU? I became frantic for air. I had just seen her on Friday and she was fine. How could she be in the ICU on Monday? I ground the sticky plastic of the telephone into my ear, struggling to absorb the story that was being transmitted.

On Saturday, George told me, Mercedes had experienced another headache. On Sunday her headache worsened so she came to the ER. Nothing was found on physical exam and she was sent home with a diagnosis of ‘post-meningitic headache,’ a frequent phenomenon.

On Monday, this afternoon, she complained of the ‘worst headache of her life’ accompanied by nausea and vomiting. She returned to the ER and this time she was admitted to the hospital. The doctors who spoke with her said she was able to give a coherent history of her recent treatment, and again had a perfectly normal neurological exam. Nonetheless, they sent her for a CT scan of her head.

On Monday, this afternoon, she complained of the ‘worst headache of her life’ accompanied by nausea and vomiting. She returned to the ER and this time she was admitted to the hospital. The doctors who spoke with her said she was able to give a coherent history of her recent treatment, and again had a perfectly normal neurological exam. Nonetheless, they sent her for a CT scan of her head.

The CT scan lasted about fifteen minutes. When the technician went to help her out of the scanner, he found her unresponsive. A code was called, but by the time the code team arrived her pupils were already fixed and dilated: a sign of irreversible brain swelling. She was brought to the ICU where a hole was drilled in her skull in attempt to relieve the pressure, but it was too late.

Steroids were given to decrease the inflammation. Antibiotics of every stripe were administered. Various maneuvers to lower her intracranial pressure were attempted – artificially increasing her breathing rate, angling the bed to keep her head above her feet, infusing massive doses of osmotic diuretics – but none worked. Now she lay in Bed 10 of the ICU, her breathing maintained by a ventilator…brain dead.

Tests for tuberculosis, lupus, syphilis, vasculitis, and other inflammatory diseases were performed and all were negative.

“Could this all be from the Lyme?†I stammered, the tortilla crumbs petrifying my tongue.

“Nah,†George replied. “We sent another Lyme titre and it came back negative. This ain’t Lyme.â€

The Lyme test was negative?

“Yeah, the first Lyme was a false positive,†George said. His voice faded for a minute as he told one of the nurses to suction Bed 4.Â

How could this whole thing have happened? How could a young woman, whom we had presumably cured, who had been so alive and healthy three days ago, be brain dead now?

I stormed back and forth in the two rooms of my apartment, crashing up against the infernally cramped dimensions that pass for living space in Manhattan. I called a pulmonologist that I knew and paged two of my residency colleagues but the case didn’t make any sense to them. I tore my textbooks off the shelves, ripping through the indices for answers. I upended the contents of my ‘Mercedes / Lyme’ folder, scouring the fine print in the scientific papers, hurling them aside when they proved useless.

Lyme in the inner city? How could I have been such an idiot to believe those results? A false positive – how could I have been so stupid?

This could not be happening. This Mercedes could not be the same as the Friday Mercedes who’d smiled at me when I shook her hand. The Friday Mercedes was real. This Monday Mercedes was just a case report over the phone. It couldn’t be real.

This could not be happening. This Mercedes could not be the same as the Friday Mercedes who’d smiled at me when I shook her hand. The Friday Mercedes was real. This Monday Mercedes was just a case report over the phone. It couldn’t be real.

Should I go over to Bellevue to see? Should I verify in person what I’d been hearing over the phone? But the neurosurgeons were already there and the head of the infectious disease unit had personally examined Mercedes. She was already receiving the best nursing and medical care available. In reality I knew that there was nothing I could add. Everything would still be the same on morning rounds a few hours from now. Anyway, I might be overstepping my bounds if I went in at this late hour, somehow insinuating that George’s care was inadequate. Besides, once the pupils are fixed and dilated, everyone knows that there is nothing else to do.

It was now 2:00 a.m. I couldn’t sit still and I’d run out of friends who I could call at that hour. I tried to convince myself that it would be for the greater good of all my patients if I just calmed down and got a good night of sleep so I could function in the morning. But my hands wouldn’t stop shivering and I had already eaten all the chocolate I could unearth in my apartment.Â

I pulled on an old pair of scrubs and set off down First Avenue. The street was quiet – even the homeless had gone off somewhere to sleep. The gloomy brick behemoths of the old Bellevue buildings cast spooky shadows in the moonlight. The decaying TB sanatorium and mental hospital menaced from behind tall cast-iron gates. The dusky ivy on the brick buildings gave the walls a moist, velvety appearance. The scalloped columns in the abandoned courtyard poked eerily out of the ground like portals into some dark netherworld. I made my way through the midnight heaviness, my feet only vaguely aware of the sidewalk beneath them. From the faint lights in the garden I could just see the dark shadows that were the sundial and fountain.

But inside the hospital building it was brightly lit. I squinted at the shock of light as I walked down the long white hallways, past the closed coffee shop, past the darkened candy store, past the sleepy security guard. I felt blurry from the incongruity of it all – the Mercedes that I had seen on Friday had disappeared and a new one had been substituted. How could normal hospital life go on when such unearthly alchemy was occurring in its midst?

I tiptoed into the ICU. From the doorway I saw George facing Mercedes’ family and friends who were gathered around Bed 10. I edged in closer, but the bed was obscured by the people standing around it. George was trying vainly to explain the finality of the situation. Mercedes’ mother and two sisters were sobbing openly. Her brother stood motionless, his eyes occasionally quivering within his otherwise frozen expression of bewilderment. Some friends clustered around the sisters, hugging them and weeping.

I tiptoed into the ICU. From the doorway I saw George facing Mercedes’ family and friends who were gathered around Bed 10. I edged in closer, but the bed was obscured by the people standing around it. George was trying vainly to explain the finality of the situation. Mercedes’ mother and two sisters were sobbing openly. Her brother stood motionless, his eyes occasionally quivering within his otherwise frozen expression of bewilderment. Some friends clustered around the sisters, hugging them and weeping.

I hovered by the supply cart, forcibly swallowing against the sticky walls of my throat. In the surreal penumbra of the ICU, the family blended into a landscape of backs, with shadowed peaks and dips surrounding a central canyon. The fluorescent lights from the bed arose within their mountainous midst and glinted up off their faces, creating awkward silhouettes and oddly sculpted canyons. I crept closer to the rocky human formation, hoping that no one would notice me. The light within drew me forward with a queasy gravitation. I had to see what was inside. The air seemed to thin out as I drew closer and I had to work harder to breathe. As I neared the bed my stomach rebelled and I placed a hand on it to keep it down. A rivulet of yellowish-green light seeped from between the mother and one of the cousins. I squinted into the crack of light to see what lay in Bed 10.

It was Mercedes, the one that I knew.

It was the same Friday Mercedes, with luminous cheeks and luxurious black hair cascading on the pillow. Her eyelids were softly closed and the dark lashes rested in delicate parallel lines upon her olive cheeks. Her gold filigree cross floated along the plump, unblemished skin of her neck. Her respirations calm and even, thanks to the ventilator. Aside from the breathing tube, she looked like a beautiful, healthy woman who was only sleeping.

From the electronic monitors overhead, though, a different story was evident. The red line indicating the pressure inside of Mercedes’ head was undulating menacingly at the edge of the screen, nearly off the scale entirely. Despite all of the medical interventions, her brain was swelling inside the solid walls of her skull. A pressure chamber was roiling inside those unforgiving cranial bones, driving the base of her brain out the bottom of her skull. The respiratory center of her brain had already been trampled by the relentless onslaught. The cardiac center would soon follow.

How could this be my Friday Mercedes?

The brother noticed me standing behind the crowd and then the whole family turned to me. Nobody said anything, but I could feel the desperation of their eyes, those longing eyes, beseeching me to offer them something that hadn’t yet been tried. But I was still trying to reconcile my own reality. I was still trying to convince myself that this was the same Mercedes I’d known on Friday. That this beautiful, sleeping woman was the same woman we’d so triumphantly diagnosed with Lyme disease only three weeks ago.

And now brain dead. All because I’d sent that damn test.

Usually when I’ve had to explain to a family that a patient is dying, the patient graciously assists me by looking the part. They are pale or emaciated, or in pain, or struggling for breath: they look like death. But Mercedes refused to play along. Serenely she lay, as beautiful as she’d been three days ago: no scars from repeated IVs and blood draws, no skin ulcers from prolonged immobility, no dull coating of the skin from weeks of not seeing the sun. No, she looked steadfastly alive.

But she was dead. Brain dead is dead. There is no gray area in brain death. Mercedes’ ‘lifefulness’ was just an illusion granted by the ventilator and the short duration of her condition. In a day or two her body would swell up and her skin would grow dusky. The cardiac center of her brain would be smothered by the persistent intracranial swelling and her heart would finally give out. Then Mercedes would look like the death that we knew and our senses trusted.

The hospital chaplain arrived. He was a rotund, balding, Catholic priest whom I had seen around the hospital but never met. A Bellevue ID card and a wooden crucifix dangled from his neck. They settled on the flare of his belly, competing with each other for prominence as he moved about. He slowly made his way around the bed, touching each family member, offering tissues, murmuring softly. I could see each person’s body relax ever so slightly at his touch. With his pudgy white hands he seemed to spread soft dapples of comfort. His job looked so much more palatable than mine. How simple just to be the bearer of solace.

The hospital chaplain arrived. He was a rotund, balding, Catholic priest whom I had seen around the hospital but never met. A Bellevue ID card and a wooden crucifix dangled from his neck. They settled on the flare of his belly, competing with each other for prominence as he moved about. He slowly made his way around the bed, touching each family member, offering tissues, murmuring softly. I could see each person’s body relax ever so slightly at his touch. With his pudgy white hands he seemed to spread soft dapples of comfort. His job looked so much more palatable than mine. How simple just to be the bearer of solace.

He glanced at me from across the bed where he was standing with one of the sisters and he must have seen a tear welling up in my eye. He circled back to where I stood and silently he reached out his arm and rested it upon my shoulder. The gentle weight settled onto my shoulder blades. It absorbed into the strain of my back, melting the muscles that were clenching and smothering me. My stethoscope twisted off my neck onto the floor as I leaned into his black tunic and began to cry. His arms circled around me and my body reacted to that touch, unraveling and letting go. I collapsed deeper into his chest, sobbing and sobbing. The family stared with quiet amazement as I cried uncontrollably in the arms of a strange priest. One of the sisters left Mercedes’ side and came to me. She stroked my back, her fingers running along my hair.

I cried for Mercedes. I cried for her family and her two little children. I cried for all my patients who had died during my ten years at Bellevue. I cried for the death of my belief that intellect conquers all.

When I ran out of tears and stamina, I said quiet, embarrassed good-byes to Mercedes’ family. The older sister handed me my stethoscope. She took my hand, looked me straight in the eye, and said ‘thank you’ with such sincerity that I felt guilty. Her sister was dying and instead of me comforting her, she was offering comfort to me.

I stumbled out of Bellevue in a daze. It was raining and I didn’t have an umbrella. Dawn hadn’t yet risen over the East River, but the air was lighter. I was exhausted, but felt strangely relieved. That uncontrollable nervous energy had finally abated and the drenching rain felt cleansing.

I stayed up the rest of the night and wrote down as much about Mercedes as I could remember. For the first time in my ten years of medical training, sleep did not interest me.

Four weeks later I completed my internal medicine residency. My ten years at Bellevue had finally ended. There was little pomp as I limped out of the ICU all alone on a rainy Sunday morning after my final thirty-six-hour shift. Bed 2 was coding, but somebody else was taking care of it.

Four weeks later I completed my internal medicine residency. My ten years at Bellevue had finally ended. There was little pomp as I limped out of the ICU all alone on a rainy Sunday morning after my final thirty-six-hour shift. Bed 2 was coding, but somebody else was taking care of it.

My body drooped with exhaustion, its muscles depleted and quivering from the mere effort of walking. And my soul felt drained, aching for rest. I couldn’t think beyond unloading these 206 bones into a soft, warm, horizontal bed. I couldn’t fathom opening a newspaper tomorrow, much less starting a fellowship or a job, like most of my colleagues were doing. I needed repose.

I knew that I had to get out of Bellevue, even if for just a little while – away from residency, away from training, away from death. I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do, but I knew I had to do something different. There would always be decades of medicine awaiting me, but there might never be another time to slip away, to uncurl, open up. I signed up with a locum tenens agency that would allow me to do short-term medical jobs anywhere in the country – after a two-month summer break, of course. I planned to work only one month at a time, and then travel as far as the money would take me. I wanted to go to Central America to see the native countries of so many of my patients at Bellevue. I wanted to learn the language that had prevented me from communicating with them. And I had to write down my stories from Bellevue.

I purchased a laptop computer that fit into my backpack. I stocked up on as many novels as I could carry, and cancelled my subscription to the New England Journal of Medicine.

But Mercedes continued to haunt me. For the next two years, between my travels and my locums assignments, I cornered every neuropathologist who could spare a moment to hear her story. I faxed her case history to experts at different medical centers and hounded them with phone calls, but no one had an answer for me. Mercedes’ autopsy was ‘unrevealing’ and every test was negative or ‘nondiagnostic.’ The medical examiner eventually signed the case out as ‘unknown etiology.’Â

Something had killed Mercedes, why couldn’t we figure it out? How come, with all of our CT scans, intracranial monitors, immunologic assays, and third-generation antibiotics, a young healthy woman could walk into the hospital with a headache and then be dead within hours? I may as well have applied amulets and recited incantations. Ten years of training, of memorizing complex formulas, of cramming differential diagnoses – blithely squelched by some anonymous microbe. None of my professors had ever prepared me for this. None of my textbooks had ever talked about this. None of the diagnostic algorithms that we discussed on rounds had ever taken this into account. None of the multiple choice questions on our board exams ever offered this as a possible answer. There was no academic medical subspecialty dedicated to this.

Something had killed Mercedes, why couldn’t we figure it out? How come, with all of our CT scans, intracranial monitors, immunologic assays, and third-generation antibiotics, a young healthy woman could walk into the hospital with a headache and then be dead within hours? I may as well have applied amulets and recited incantations. Ten years of training, of memorizing complex formulas, of cramming differential diagnoses – blithely squelched by some anonymous microbe. None of my professors had ever prepared me for this. None of my textbooks had ever talked about this. None of the diagnostic algorithms that we discussed on rounds had ever taken this into account. None of the multiple choice questions on our board exams ever offered this as a possible answer. There was no academic medical subspecialty dedicated to this.

What will Mercedes’ children think of the medical profession, I wondered. Their mother, of whom they’ll have only dim recollections, had died mysteriously and the doctors never knew why. I wanted to go to them and apologize for our shortcomings, our limited intellect, our inadequate tools, the false pride that led us down the wrong path, our utter failure. But they are in their own world, being raised by a loving, extended family.

And while I was intellectually frustrated, I felt strangely emotionally complete. That night in the ICU with Mercedes was excruciatingly painful, but it was also perhaps my most authentic experience as a doctor. Something was sad. And I cried. Simple logic, but so rarely adhered to in the high-octane world of academic medicine. Standing in the ICU, the chaplain’s arms around me, surrounded by Mercedes family, I felt like a person. Not like a physician or a scientist or an emissary from the world of rational logic, but just a person. Like each of the other persons who were locked in that tight circle around Bed 10. There was a strength in that circle that I’d never felt from my colleagues or my professors. A strength that allowed me to release the tense determination for intellectual mastery that had so supported me as a doctor. After years of honing those muscles, it was a deliriously aching relief to let them go.

And it didn’t turn me away from medicine; it enticed me. I did need a break, but I knew that I would come back. I still wanted to learn more and become a smarter doctor, but I also wanted to be in this world populated with living, breathing, feeling people. I wanted to be in this sacred zone that was alive with real feelings, theirs and mine. I still didn’t know why I had initially entered the field of medicine ten years ago, but I now knew why I wanted to stay.

And it didn’t turn me away from medicine; it enticed me. I did need a break, but I knew that I would come back. I still wanted to learn more and become a smarter doctor, but I also wanted to be in this world populated with living, breathing, feeling people. I wanted to be in this sacred zone that was alive with real feelings, theirs and mine. I still didn’t know why I had initially entered the field of medicine ten years ago, but I now knew why I wanted to stay.

“Merced†won the Editor’s Prize for Nonfiction in The Missouri Review, and then appeared in Best American Essays, 2002. It was then incorporated in Danielle’s first book Singular Intimacies: Becoming a Doctor at Bellevue. (Beacon Press, reprinted with permission.)